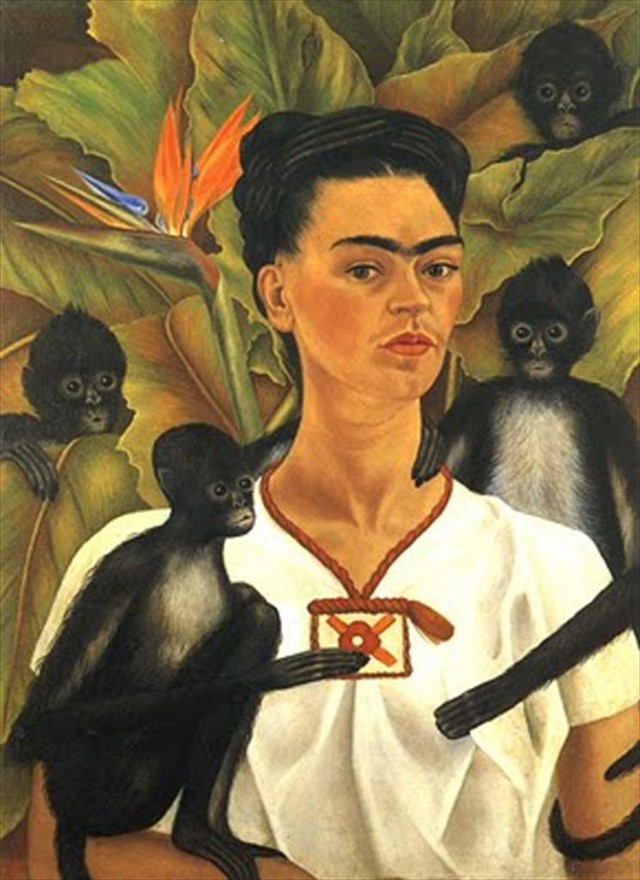

I’ve been thinking a lot about Frida Kahlo lately, as I’ve been asked to speak at the Art Gallery of South Australia’s panel on Frida’s feminist legacy later this week, as part of their “Frida & Diego: Love & Revolution” exhibition. Today, incidentally, is her birthday.

Turning my attention to Frida is a return to childhood for me, when she was a key source of comfort. This was during the rise of “Fridamania”: which spanned from influencing designers like Gaultier in the 1990s, to Salma Hayek’s 2002 biopic, and being famously loved by Madonna in this period. But from memory it wasn’t pop culture so much as my mother who introduced me to Frida, and the reason? My thick monobrow.

Frida’s stoic and defiant self portraits were the only positive imagery I had of anyone with a monobrow. There was literally no other representation I could find, no Internet to search, no monobrows in magazines or on television unless there was a reference to a character being deeply annoying, ugly, sinister, or cringeworthy (despite a brief media blip about a model growing a monobrow in 2018, things definitely haven’t changed on this front).

Because of Frida I could mostly stand these depictions. Feeling self-conscious I would leaf through the accordion book of Frida’s self portraits my mother had given me, I would recall her paintings that I had seen myself at the National Gallery in 2001. In primary school I would pre-empt scorn by joking to people “I can raise one eyebrow, wanna see?!”

Despite her psychic assistance, and even as Frida’s star image was rising in the popular imagination, the hegemony of two-brow dominance was too much to bear by the time I reached high school. As a teenager Frida came to feel like an awkward relative I didn’t want to associate with, or shameful interior self. I plucked her away, pruning my hair back to little and far-apart slugs.

Seeking repair for my zealous plucking, I went to a beautician and explained. I remember saying “you must see a lot of monobrows” and she just looked at me blankly. It’s a memory soaked with humiliation, and looking back at the pictures of myself in these period fills me with profound sadness, the shame with which I carried my body in the world as if I wanted to hide away.

I have been particularly horrified to find that several of the popular books for sale about Frida today (such as “Frida: A to Z“) depict Frida with two eyebrows, and certainly no moustache. This is in spite of the fact that these publications explicitly contain sections discussing the significance of Frida’s monobrow and hair to her constructed image: the way she would enhance her brow with pencil and gel, and emphasise her facial hair in her portraiture.

Perhaps the artistic teams on these books missed the memo, but it seems to me as if she’s been run through a filter of palatability, to suggest that her star as a style icon is only possible by bringing her closer to white patriarchal femininity rather than representing her subversive femme Mexican self-construction. Similarly, when a Barbie version of Frida was released in 2018, she was given a barely-there brow, whitened skin, and an inauthentic style of dress.

The circulation of Frida’s image today feels like a photocopy of a photocopy, a girl-boss-ification that focuses on her glamour, with occasional side notes on her sexual and gender queerness, communism, or pain. She’s on tote bags and tarot decks, and children’s books that simply note her posthumous triumph as an icon. Whether the monobrow is there on not, Frida the artist is often stripped away in favour of Frida the pop-art-like screen print.

Returning to Frida as an adult I feel desperate to understand her, to appreciate her in her complexity and for her artistry. To be as bold as her. As a child I didn’t understand the weight behind Frida’s bloody and bodily paintings, that it wasn’t all about her face. I didn’t comprehend Frida’s accident as a teenager, her chronic pain, infertility and child loss, the importance of her Mexican identity, her communism, her bisexuality, even though so much of this is communicated in her paintings. Recently I bought my young daughter a children’s book about Frida, and though the monobrow is there, the retelling is saccharine: Frida was sad in some of her paintings, but smiling in others! Frida loved life! What does it take to be a feminist icon? Why is it so hard for pain, queer love, loss, to be part of the narrative?

I suspect that even if I had understood Frida more holistically as a child, as more than her monobrow, it would not have been enough to keep the tweezers away.

I sit here fantasising about a future monobrow, un-waxing Frida. I fear there is a gap now that can never grow back.