Note: The below review contains spoilers for the Barbie (2023) film! If you’d like a discussion that is spoiler-free (recorded before the film screened), check out my chat about bimbos and Barbies on NPR’s It’s Been a Minute with Brittany Luse.

I went and saw Barbie on opening night, and walked right back in and saw it again the next day. The hype around the film has been so immense that I felt like I was holding my breath with excitement and expectation for the whole first screening. Because Barbie is essentially two movies in one mashed together (Barbie and Ken’s stories), as well as kind-of but not-quite being a musical, and definitely a technicolour spectacle, the net result of my first viewing was overwhelm. When I saw it the next day everything made more sense, I knew what to expect. It was much more enjoyable and I highly recommend seeing it twice (or more…I’ll definitely go back).

Despite the long lead up to the film’s release, and literally months of speculating about its content, I found Barbie to be so unexpected, joyously unique. I guess even with all my queer hopes I still thought that the film would be more like a traditional blockbuster, with a romantic narrative, or some easy arc to follow. What it actually feels like is an indie director being given the keys (and money) to make an expansively imaginative film, which is exactly what it is! However in being bold it was also sometimes messy, mostly because it was two distinct stories running in parallel: 1) A comedy drama about Stereotypical Barbie becoming human (an inversion of the typical moral panic around Barbie that human girls will try and become like her); AND 2) A musical about Beach Ken grappling with male entitlement and an inferiority complex. Quite different stories in both message, arc, and tone. When Ken walks off in the real world (to stumble across patriarchy), the film splits into two.

Ironically, comically, I hadn’t thought about Ken, or what his storyline might have to say about gender AT ALL in the lead up. What Gerwig gives us is a very funny meditation on contemporary white masculinity and patriarchy. Honestly Ken’s line that he wasn’t that interested in patriarchy when he realised it wasn’t about horses was so funny, I’ll be laughing about this for the rest of my life. I’ve been listening to “I’m Just Ken” on repeat. Will I buy some “I am Kenough” merch? Uh, yes. Gosling’s Ken, and the whole storyline almost steals the show from under Barbie’s flat feet, but Margot Robbie is so incredibly earnest in her performance that it’s really just a two-pronged circus the whole way through. I do wish Barbie got an equally big musical number to balance it out a bit though.

What is so wonderful about all of the scenes with the Barbies and Kens is how playful they are – as in, literally so silly that it reminds me of playing with toys as a child. The whole Ken fight scene is ridiculous but I can also completely imagine setting that up as a kid, having a war of Kens, on a beach, that turns into a Grease-like dance off where the Kens also kiss. 100% accurate.

The bits that truly sucked in the film were everything with the humans. The parts with the Gloria/Sascha mother/daughter storyline were so two-dimensional, mere props to further the Barbie storyline. Terrible lines. The most asinine feminist speech you can imagine. Inexplicable reactions (like when Sascha first meets Barbie). And the Ruth Handler saccharine ghost stuff? Just the worst. The Mattel humans were less boring, but really because they were more like the toys of the film, silly and hammed up, part of the melodrama, rather than boring interruptions.

I’ve also seen some critiques of the film along the lines of: this Barbie is capitalist. Gerwig tries to double-play the issue of Barbie as a consumer product, with the film nodding and winking to itself the whole way through. This is such a cheap (pun) shot at the film, because what else was Gerwig supposed to do? There is no way to make this film without that critique being levelled. I do think that this hyper-concern over consumption is reserved especially for things associated with femininity though. When the Lego film came out everyone just marvelled at its unexpected communist undertones, and then went and played with Lego. They didn’t bemoan the Lego industrial complex.

Perhaps most importantly (given my projections) the real question is: how queer and feminist is the Barbie film? Well, in terms of its internally stated feminism: lacklustre. We see some lowest common denominator feminism in the dialogue, and interestingly though patriarchy is referred to throughout, the f word is rarely mentioned as an explicit antidote. If I was writing the script, I would have had Gloria the human give the Barbies some 1970s feminist books and start consciousness-raising groups to get them out of their brainwashing, but perhaps this is just my very specific taste as someone who lectures on gender (edit: as a friend pointed out, they kind of try to do this but for a general audience — but what I’m trying to say is it’s consciousness-raising lite!). In spite of this, my hope that this film could – ought to – usher in some feminist media analysis that takes femininity seriously rather than dismissing the text as postfeminist still stands. I would also like to see Ken’s arc analysed here using critical femininity studies, not simply deferring to masculinity studies as the place to explain what is represented (perhaps another post, for another time…).

The queerness of the film is stitched into its very fabric, and not just because loads of the cast are LGBTQ+. Though Stereotypical Barbie doesn’t get to make out with any other Barbies (I would have appreciated at least ONE scissoring joke) the implication is certainly that she is queer, because she is queer-coded. From Birkenstocks, to listening to Indigo Girls, to not being interested in Ken, to identifying with “Weird” Barbie, and the Barbie cinema playing Wizard of Oz (all Barbies are “friends of Dorothy”?), the strong hint is that Barbie is not straight. “Weird” Barbie is clearly a euphemism for Queer Barbie, not least because she is played by the famously gay Kate McKinnon, and the rag-tag team she assembles in her house when patriarchy takes over Barbie land also indicates that they are a queer bunch. From Allan (Ken’s “friend”) to Magic Earring Ken and Video (aka Cyborg) Barbie, these are the queer crew, discontinued by Mattel. By the end of the film, after their power-to-patriarchy-and-back-again journey the vibe seems to be that all of the Barbies are “weird”.

Yet it is also the transness of Barbie that comes to the fore at the very end when she realises her humanness, rather than (as Ruth tells her) having to “want” or “ask” for it. I read this as a trans allegory, where Barbie’s true self is not something she “identifies” as, but something she affirms: she just is. That the last scene involves her visiting a gynaecologist furthers this reading. We don’t know how or when Barbie got a vagina, but she’s so pleased to have one. This doesn’t seem to be a regressive suggestion, that all women ought to have certain biology – and the fact that we learn Ruth had a double mastectomy seems relevant here – but that Barbie realised she was a woman, and wanted certain genitals, which she got. I truly hope this sends the trans-exclusionary activists out there into a tailspin.

Five stars, plenty of notes, but a film I will absolutely cherish forever.

Bisexuals (and especially bisexual men) have often been seen to “contaminate” straight life. This was most explicitly seen in the midst of the AIDS crisis, during which bisexuals were represented as adulterous hyper-sexual types who risked spreading the disease to the “normal” population. Similarly, gay communities have rejected bisexuals as “risky”, as seen in the 1990s following a rise in homophobic street attacks when the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras effectively

Bisexuals (and especially bisexual men) have often been seen to “contaminate” straight life. This was most explicitly seen in the midst of the AIDS crisis, during which bisexuals were represented as adulterous hyper-sexual types who risked spreading the disease to the “normal” population. Similarly, gay communities have rejected bisexuals as “risky”, as seen in the 1990s following a rise in homophobic street attacks when the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras effectively

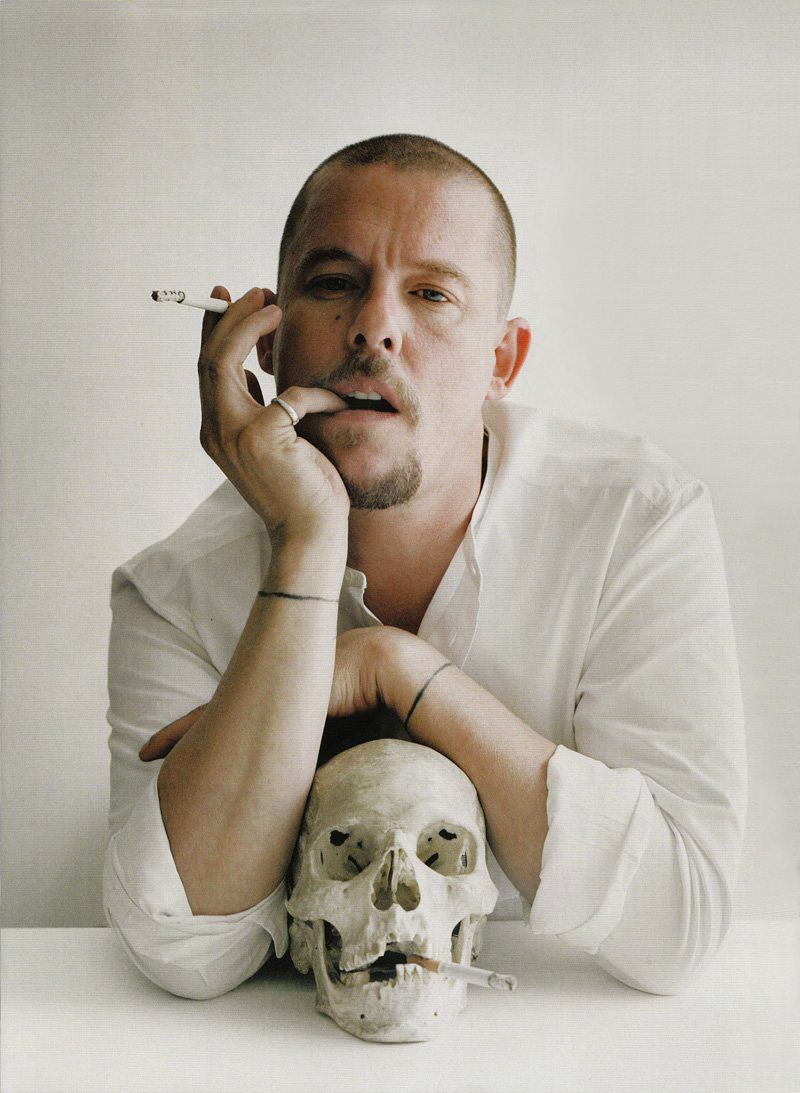

Yet, Lee Alexander McQueen’s vision of the possibilities of fashion to affect us on a profound emotional level juxtaposes such critiques. Tracking the autobiographical aspects of McQueen’s design, this documentary offers us a sense of artistry that cuts through ordinary understandings of fashion in terms of trends, mass production, and surface.

Yet, Lee Alexander McQueen’s vision of the possibilities of fashion to affect us on a profound emotional level juxtaposes such critiques. Tracking the autobiographical aspects of McQueen’s design, this documentary offers us a sense of artistry that cuts through ordinary understandings of fashion in terms of trends, mass production, and surface. McQueen described his shows as “what’s buried in people’s psyches”. One of the things that I love most about this documentary is the use of home footage from McQueen himself, which offers us an intensely intimate glimpse of the designer. We not only get a sense of McQueen’s mind – and his obsession with death, life, and beauty – most importantly I think, we get to see the tyranny of maintaining creativity despite the stifling economics of fashion.

McQueen described his shows as “what’s buried in people’s psyches”. One of the things that I love most about this documentary is the use of home footage from McQueen himself, which offers us an intensely intimate glimpse of the designer. We not only get a sense of McQueen’s mind – and his obsession with death, life, and beauty – most importantly I think, we get to see the tyranny of maintaining creativity despite the stifling economics of fashion. McQueen once said, “My sister is an amazing artist. My brother is an amazing artist. Amazing. Much better than I am. The difference is, they thought they had no chance but to do a manual job. That really upsets me”. To survive as a designer early in his career, McQueen had to live on almost nothing, and hide his fashion work from the dole office so that he could continue receiving benefits.

McQueen once said, “My sister is an amazing artist. My brother is an amazing artist. Amazing. Much better than I am. The difference is, they thought they had no chance but to do a manual job. That really upsets me”. To survive as a designer early in his career, McQueen had to live on almost nothing, and hide his fashion work from the dole office so that he could continue receiving benefits. To quote Elizabeth Wilson again, “Out of the cracks in the pavements of cities grow the weeds that begin to rot the fabric”. In other words, while we might hold reasonable ambivalence about the nature of fashion in terms of the expectations and norms that it reproduces, fashion can also provide an experimental and resistant space for a creative reimagining of identity that “rot[s] the fabric” of these same rules.

To quote Elizabeth Wilson again, “Out of the cracks in the pavements of cities grow the weeds that begin to rot the fabric”. In other words, while we might hold reasonable ambivalence about the nature of fashion in terms of the expectations and norms that it reproduces, fashion can also provide an experimental and resistant space for a creative reimagining of identity that “rot[s] the fabric” of these same rules.

While the closure of the film was a little clunky (and I wondered if they actually had a few different endings in mind), overall First Girl I Loved is utterly engrossing. The opening scenes are framed tightly and closely around the protagonists, and we remain at eye level, almost as if we are right there with them – behind the softball fence, lingering at the doorway to the bedroom, walking down the street sipping $4 wine. We’re next to them all the way, not as a voyeur, but as a friend along for the ride.

While the closure of the film was a little clunky (and I wondered if they actually had a few different endings in mind), overall First Girl I Loved is utterly engrossing. The opening scenes are framed tightly and closely around the protagonists, and we remain at eye level, almost as if we are right there with them – behind the softball fence, lingering at the doorway to the bedroom, walking down the street sipping $4 wine. We’re next to them all the way, not as a voyeur, but as a friend along for the ride. Gelula’s performance is very commendable. She strikes a delicate balance between unbearable apathetic teen, and captivating hero that we want to succeed. Through Anne we see just how brilliant and strong teens can be, even if they’re totally clueless. Teens are often denigrated by society writ-large for being naive, but First Girl I Loved shows the pain and beauty of fumbling through, the intelligence involved in not knowing but pushing on nonetheless. The awkward innocence of Anne and Sasha’s interactions is wonderfully executed, and there was something so familiar about their veiled giggling banter that I felt like I was watching my young self up on screen.

Gelula’s performance is very commendable. She strikes a delicate balance between unbearable apathetic teen, and captivating hero that we want to succeed. Through Anne we see just how brilliant and strong teens can be, even if they’re totally clueless. Teens are often denigrated by society writ-large for being naive, but First Girl I Loved shows the pain and beauty of fumbling through, the intelligence involved in not knowing but pushing on nonetheless. The awkward innocence of Anne and Sasha’s interactions is wonderfully executed, and there was something so familiar about their veiled giggling banter that I felt like I was watching my young self up on screen. As I sat watching the film unfold, I found myself desperately wanting things to work out for the characters. I wanted it to end happily not only because I was so engrossed in the story, but because happy endings for gay characters are so few and far between. It’s been great to see more films coming out that address romance between women, like

As I sat watching the film unfold, I found myself desperately wanting things to work out for the characters. I wanted it to end happily not only because I was so engrossed in the story, but because happy endings for gay characters are so few and far between. It’s been great to see more films coming out that address romance between women, like  While I can imagine some queer theorists arguing that the lack of traditionally happy endings for gay films is welcome, because who wants to live up to that heteronormative expectation anyway, it’s also pretty shit to constantly have popular culture either ignore your relationship or portray it is an inevitably difficult affair. While there is something to be said for representing the reality of homophobia and the difficulty of queer life, it is a pain that everyone else gets the option of fantasy (because let’s be real it’s not like heterosexual life really ends happily for everyone) except for gays who must remain proper realists.

While I can imagine some queer theorists arguing that the lack of traditionally happy endings for gay films is welcome, because who wants to live up to that heteronormative expectation anyway, it’s also pretty shit to constantly have popular culture either ignore your relationship or portray it is an inevitably difficult affair. While there is something to be said for representing the reality of homophobia and the difficulty of queer life, it is a pain that everyone else gets the option of fantasy (because let’s be real it’s not like heterosexual life really ends happily for everyone) except for gays who must remain proper realists. First Girl I Loved is no romcom, and it is serious. But it does manage to deal with difficult issues and give us a sense of both catharsis and hope, even as it leaves many things unresolved. It doesn’t make the empty promise that so many teens are barraged with that “it gets better”, but it does suggest that queer kin can be found and that inner strength is possible while traversing difficult and unknown terrain. First Girl I Loved gifts its audience a small beam of light for navigating this path, and for that it should be celebrated.

First Girl I Loved is no romcom, and it is serious. But it does manage to deal with difficult issues and give us a sense of both catharsis and hope, even as it leaves many things unresolved. It doesn’t make the empty promise that so many teens are barraged with that “it gets better”, but it does suggest that queer kin can be found and that inner strength is possible while traversing difficult and unknown terrain. First Girl I Loved gifts its audience a small beam of light for navigating this path, and for that it should be celebrated.

The first is from trans-exclusionary radical feminist types, who conflate gay male culture with drag queens with transgender identity. Such perspectives see gay men, drag queens, and trans women as responsible for propping up fantasies of femininity that only serve to oppress women. Germaine Greer famously stated in The Female Eunuch 1970: “I’m sick of being a transvestite. I refuse to be a female impersonator. I am a woman, not a castrate”. Greer’s suggestion here is that there is some form of “natural” womanhood that can be liberated from the dictates of culture. Similarly, and more recently, Sheila Jeffreys has even argued that drag kings distort lesbian culture and the celebration of “natural” womanhood. She writes: “If the suffering and destruction of lesbians is to be halted then we must challenge the cult of masculinity that is evident in such activities as drag king shows”. These views are rife with homophobia and transphobia, as well as massive conflations and wild leaps that see men, masculinity, and femininity, as the true oppressors of women.

The first is from trans-exclusionary radical feminist types, who conflate gay male culture with drag queens with transgender identity. Such perspectives see gay men, drag queens, and trans women as responsible for propping up fantasies of femininity that only serve to oppress women. Germaine Greer famously stated in The Female Eunuch 1970: “I’m sick of being a transvestite. I refuse to be a female impersonator. I am a woman, not a castrate”. Greer’s suggestion here is that there is some form of “natural” womanhood that can be liberated from the dictates of culture. Similarly, and more recently, Sheila Jeffreys has even argued that drag kings distort lesbian culture and the celebration of “natural” womanhood. She writes: “If the suffering and destruction of lesbians is to be halted then we must challenge the cult of masculinity that is evident in such activities as drag king shows”. These views are rife with homophobia and transphobia, as well as massive conflations and wild leaps that see men, masculinity, and femininity, as the true oppressors of women. I don’t have much time for these views, which encourage us to believe that the biggest threats to women are trans women, drag queens, and gay men. This view distorts Marxist theory to argues that men in particular are *the* class that oppresses women, and sees the liberation that is to be won as a liberation from “gender”. Luckily the currency of radical feminism in academic spaces seems to be waning. But when overall activist struggle in society is low, it is easy for people to slip into arguing that we are each other’s problem, that if only we could free ourselves from gender we’d be truly liberated. It’s a much easier argument to make than organising to transform the fundamental economic arrangement of society, and it makes space for all kinds of class collaboration between powerful women and poor women alike (even if it means at the end of the day that power doesn’t actually shift).

I don’t have much time for these views, which encourage us to believe that the biggest threats to women are trans women, drag queens, and gay men. This view distorts Marxist theory to argues that men in particular are *the* class that oppresses women, and sees the liberation that is to be won as a liberation from “gender”. Luckily the currency of radical feminism in academic spaces seems to be waning. But when overall activist struggle in society is low, it is easy for people to slip into arguing that we are each other’s problem, that if only we could free ourselves from gender we’d be truly liberated. It’s a much easier argument to make than organising to transform the fundamental economic arrangement of society, and it makes space for all kinds of class collaboration between powerful women and poor women alike (even if it means at the end of the day that power doesn’t actually shift).

So that’s why it’s kind of surprising to hear people within queer communities suggesting now that drag, in its mainstream formations, is a problem. From this perspective drag, if performed by ostensibly

So that’s why it’s kind of surprising to hear people within queer communities suggesting now that drag, in its mainstream formations, is a problem. From this perspective drag, if performed by ostensibly