Nostalgia: it’s all the rage

The desire for nostalgia is a funny thing. Studies have found that you’re more likely to seek out nostalgia when you’re feeling down, particularly when you are lonely. Perhaps that’s why society seems to have been on a full-tilt nostalgia trip for some time now: everyone is feeling pretty bummed out about the future to come, and under late neoliberal capitalism more isolated individualistic-thinking than ever before. Here we might turn to Emile Durkheim’s concept of anomie to help us. Anomie describes the state of singularity and disconnection felt as a symptom of modernity and rapid social change—anomic societies are highly individualistic and fractured. It would be interesting to take up Durkheim’s analyses of anomic societies here and see just how much financial crises and social upheavals correlate with, say, the sale of Hanson tickets.

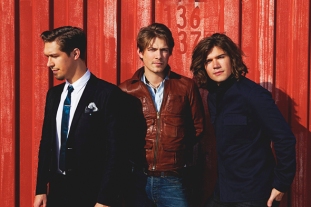

Hanson: still looking twelve years old

Going to a concert on a Monday night is strange at the best of times, and this week was certainly a bit odd when I found myself at the anniversary tour of 90s teen-pop boy-band sensation, Hanson. My friend Patrick contacted me months ago to ask me if I wanted to go, and we managed to secure tickets even though the first show had sold out in seconds. It seemed like a good idea at the time, to get a good old dose of nostalgia. But perhaps my initial response to “Do you want to go to Hanson?”—”Lol maybe!”—should have triggered me to remember: when you were a kid you didn’t actually like Hanson.

90s band Steps

Here’s the thing: I didn’t actually like Hanson. I was in year five when they got big (feel free not to do the math on that). I had just moved from a small city to a very small town, and everything I knew about what was cool, and what was what, needed to adjust. I had grown up listening to the national youth radio channel Triple J, and that was my cultural world. When I was eight (again, no math please), I remember being shocked when Kurt Cobain’s death was announced on the radio. That year was also my first concert, the Icelandic singer Bjork’s Post tour. But when I found myself in a small town (at least, in this particular small town), I found out that liking so-called “alternative” music was so not cool. Everyone was into surfing and dancing and hanging out at the beach listening to S.O.A.P. I distinctly remember being invited to a birthday party of a girl in my class and everyone knew the dance moves to 5, 6, 7, 8 by the band Steps, except for me of course. I needed to learn, and I needed to learn fast.

Smash Hits magazine was extremely useful for getting in the know

Luckily my new friend Sally who lived across the road from me knew what was what. And she was obsessed with Hanson. Sally was what they call a “completist“—someone who collects every version of every album and single and other paraphernalia released by a band. In Sally’s case this also extended to buying every magazine and newspaper that featured Zac, Taylor, or Isaac, even if it was a picture of them she already had. Her room was a shrine, perfectly plastered in a way only achievable by meticulously obsessive tweenagers. Sally’s love for Hanson eclipsed any faint glimmer of feeling I might muster myself. Plus, she owned Hanson. Zac specifically.

Nevertheless, Hanson was my gateway drug to the Top 40. I started taping songs off the radio (as you did in those days), and started listening to songs from Aqua, Spice Girls, and Savage Garden. I changed my taste, as much as I could, so at the very least I could get it when the year six girls performed to Backstreet’s Back (though where they were back from I’m still not clear) in the school talent contest, to a standing ovation. I was the Cady Heron, finally able to say “I know this song!” and I could respond “I’m Posh Spice” when someone asked me how I fitted into the scheme of things.

Jordan “Taylor” Hanson

As a skinny nerdy kid with a single mother, monobrow and noticeably second-hand school uniform, pop taste could only help me pass so much. But vindication came in year six when Sally and I performed to Hanson’s Man from Milwaukee (we had to choose this song, as Zac sung it) and we won one of the prizes. “Good job” said my crush outside the canteen, licking a chocolate Paddle Pop. “Really nice” he said, as he brushed aside his Hanson-esque long hair. Pop music was the ticket.

That was, until I was in my mid twenties, dating a musician. This was the period wherein I learned that liking pop music was so not cool. According to this theory, if it wasn’t from Seattle in the 1990s, or wasn’t electronic music created while taking a lot of stimulants, it wasn’t really music. I made mix tapes out of love but they were met with derision. I also learned that a lot of this attitude was just thinly veiled sexism and elitism. How could a woman pop singer possibly be a talented musician? Obviously that bad romance didn’t last, and I decided to embrace pop music more vehemently. But in hindsight I had spent so long worrying about taste and how to achieve it, that I had forgotten what I even liked about music in the first place.

All of this ran through my head on Monday night as I listened to the epic two-hour set from Hanson, which it turns out, is an ample amount of time for 20 years’ worth of triggered memories. I had come for nostalgia, but I had instead been faced with two decades’ worth of feelings around my inadequacies in taste.

Heather Love’s Feeling Backward

The whole thing reminded me of the point that Heather Love makes in her book Feeling Backward: we can’t always “move on” from bad experiences, in fact, it might be worth dwelling awhile in some of these feelings to see how the past is still playing out. As Love states: “It is the damaging aspects of the past that tend to stay with us, and the desire to forget may itself be a symptom of haunting”. Love is talking specifically about the feelings that haunt LGBTQ communities in thinking about the past and the need to attend to, rather than forsake, these memories. But this might also be a lesson for everyone: embrace feeling backward, remember the pain of being a misfit or misunderstood that you’d rather forget. In these memories we might learn something about who we have become, rather than looking for a fantasy hit of nostalgia that can’t ever really deliver us from the present.