This week was a dismal one for the Australian Government. One of their many low points was Prime Minister Tony Abbott (apparently also the “Minister for Women“) dismissing the newly launched No Gender December Campaign, saying “Let boys be boys, let girls be girls“. Cue gigantic face-palm.

Abbott’s remarks came in stark contrast to the point made by Greens Senator Larissa Waters who introduced the campaign in Parliament, who stated the point was to “Stop with this nonsense of marketing for boys and for girls. Toys are toys and lets let kids be kids.”

The backlash in some of the conservative press, has unsurprisingly banged this story under the headline “WAR ON BARBIE“. If you’ve read some of my previous posts on children’s toys, you’ll know that I am a fan of Barbie. Or more specifically, I have difficulty accepting campaigns against stereotypically “feminine” toys, like the time everyone got really pissed off about the femmed-up Merida doll. But aside from my critique that a lot of the children’s toy debate becomes laced with femmephobia, we still need to make sure we don’t miss the fundamental point – that children’s toys are often gendered along the binary male/female, and this is not a good thing.

Let’s step it through so you can rhetorically battle bigots if you need to:

1. What even is the “gender binary”?

The gender binary refers to the idea that gender can be neatly divided into a binary male/female. This binary is a pervasive norm, particularly in Western society (some other areas of the world treat gender differently). The idea that everyone can fit into this binary has real consequences for people whose bodies do not conform how “male” and “female” bodies “should” be.

For example, babies that are born with “indeterminate” genitalia may undergo surgery to make them “normal” to fit into one of the two categories. Estimates of this indeterminacy are as high as 1 in 100 births. This is often referred to as being intersex. Another example is in sport – you have to conform to the categories of either man or woman in order to compete, and determining this is a big issue. Many athletes are subject to “gender testing”. Here, “gender” is sometimes based on chromosomes (whether you are XX or XY), other times, levels of testosterone.

But we’re not just forced to physically conform to this binary, there are social expectations tied up with the binary that affect our ways of being and acting in the world too.

2. But wait, what is the difference between “sex” and “gender”?

Many people now make a distinction between sex and gender, with sex being described as biological features, versus gender expression, as social phenomena. As Simone de Beauvoir famously said in The Second Sex, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”. In other words, women are socialised into a second-class gender status. This fundamental distinction between sex and gender is integral to many analyses of gender – indeed it has been used by many feminist writers to show that biology is not destiny.

But this distinction is not without criticism. For example, Judith Butler argues that sex is “always already gender”, given that proclamation of sex at birth (“it’s a girl”!) assumes a gender trajectory for the child – that is, we expect that a baby without an apparent penis, who is then assigned as a girl, will grow up to be a woman. This gendering entails a set of social assumptions about what girls should enjoy, how they should dress, and how they should act. Really Butler is arguing that sex/biology are perhaps more social and constructed than we think – given that we look at a certain formation of flesh and imbue it with a whole heap of social meanings.

3. But aren’t men and women are just physically different and that is just a scientific FACT?

I’m not saying that hormones and other chemical and genetic factors mean nothing to shaping humans, but socially shaping the body to fit into expectations of the gender binary happens throughout the lifespan. Have you ever walked into a gym and seen the gender imbalance between the weights and the cardio rooms? Women are expected to be lithe and skinny, and men big and bulky, so women and men are taught to shape their bodies differently.

Men are expected to eat lots of protein (hamburgers, steaks), while women are meant to be constantly dieting (salads) which also inevitably leads to bingeing (hello chocolate). This is reflected and reproduced in advertising of food and fitness products.

And don’t get me started on brain differences. There are literally oodles of books and journal articles that go into how the brain is wired through experience (i.e. the social), and how our expectations of gender affect child development (or at the very least, how we perceive differences).

Girls are often expected to be nurturing, playing with soft toys and imagine themselves such as “nurse” or “mother”

4. Okay but what do toys have to do with it?

Expectations of gender are heavily reinforced in childhood – a critical time when children are starting to develop a sense of self and how they fit into the world. While Abbott is happy to argue that “above all else, let parents do what they think is in the best interests of their children”, as sociologist James Henslin notes, our parents and wider society are highly complicit in reinforcing particular norms.

For example, this manifests in:

- The types of clothes we are dressed in, noting that sometimes clothes change the way we move about in the world (it is difficult to climb a tree in a dress or kick a ball in sandals)

- The type of play we are encouraged to engage in – not just the kinds of toys we have, but also how rough versus nurturing we are expected to be

- The types of emotions we are encouraged to express – anger, stoicism, bravado, sadness, compassion or nurturing

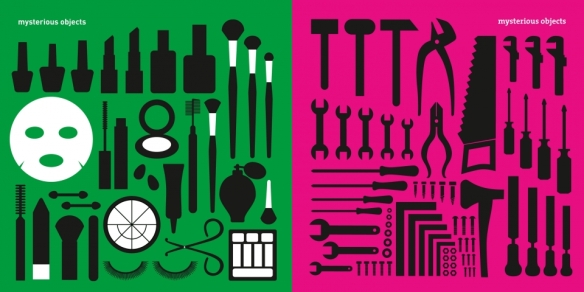

Here’s where the colour-coding of toys comes in. As you may have noticed, toy manufacturers often make toys marketed at boys blue (or primary colours yellow and red), and toys sold to girls pink (or purple, teal or pastels) and stores often separate toys according to this schema of girls vs boys toys. Thus you get aisles that are predominately blue, and ones dominated by pink. The problem isn’t the colours in themselves. The problem is the different kinds of toys that are marketed according to the gender binary, as signified by the colours chosen for the toys designated “boys” versus “girls”.

Analysing the current Toys ‘R Us catalogue, it is clear they’re making an effort to pay lip service to the gender issue – they have a boy on the front playing with a kitchen set (with the caption “just like home!”). But as you wade deeper into the catalogue, you’re met with more and more of the stereotypical stuff. Some examples of “boy” toys: space stuff, robot stuff, dinosaurs, action equipment, trains and transport, excavation and trucks, scientific equipment, pirate stuff, architecture and building, dragons, science fiction and fantasy, racing cars. And “girl” toys: dolls, princesses, woodland creatures, phones, drawing stuff, makeup, jewellery kits, accessories, fashion stuff, baby stuff, horses. It’s actually pretty crazy when you start to consider how this gendered marketing of toys might lead to the cultivation of particular interests along gendered lines, starting at a very young age.

From what I can see of the No Gender December campaign, the point isn’t to “Ban Barbie”. The point is to challenge the way in which toys are divided along the gender binary, thus reinforcing differences between how “boys” and “girls” are socialised.

In conclusion, Abbott is a bit of a jerk. But we already knew that. Did I mention that time Tony Abbott allegedly punched a wall near a rival student politician Barbara Ramjan’s head for intimidation? Or that he constantly alludes to his “hot daughters“? Or that when in opposition he continually called for Australians to “ditch the witch“, Prime Minister Julia Gillard?

Well, he might be the Minister for Women but I guess boys will be boys.