Jamila Rizvi’s recently released book Not Just Lucky is basically a very long riff on the old saying, “carry yourself with the confidence of a mediocre white man”. This is a very useful adage, which works as a reminder of the ways that women are socially conditioned. I find myself repeating this saying to women in my life frequently, and it’s useful to have a book that spends time unpacking ways that women are brought up with negative self-beliefs.

Jamila Rizvi’s recently released book Not Just Lucky is basically a very long riff on the old saying, “carry yourself with the confidence of a mediocre white man”. This is a very useful adage, which works as a reminder of the ways that women are socially conditioned. I find myself repeating this saying to women in my life frequently, and it’s useful to have a book that spends time unpacking ways that women are brought up with negative self-beliefs.

Rizvi is intent to present “solutions” not just “problems”, and so the book also provides a lot of extended advice on how to speak, dress, think, and act in ways that might get you ahead as a working woman (even though the book claims it’s not a self-help book, but a “career book”). It’s funny and well-written. I also appreciated the very organised bullet-point lists of recommendations – I daresay Rizvi and I are a similar collection of letters on the esoteric Myer-Briggs test.

Obligatory selfie of me reading Not Just Lucky

But while I found myself nodding along to many of the passages exploring the sexism that women experience in the workplace and beyond, Rizvi’s solutions fall short. What is offered is at best a band-aid to the problems described, and at worst, a cruel promise that working hard and undertaking individual self-betterment can lead to certain success.

To be fair, Rizvi acknowledges from the outset that her book doesn’t have the solutions for fixing structural problems like childcare and the wage gap, but simply offers ways women can change their thinking that has resulted from structural enculturation.

I’m on board with women undergoing some gender-CBT, heck my job is literally to talk about gender and double standards and how things we think are innate are in fact social.

I am more than ready for the “lady boss” obsession to end. Please end.

But presenting the antidote to women’s ills as endeavoring to be “brilliant” and offering a blueprint for how to succeed as a “lady boss”, is not what we need right now. In this day and age, when humans are staring extinction in the face, capitalism is in a late and hideous form, and there are right-wing forces mobilising around the world, these kind of liberal feminist solutions feel a little like over-prescribing antibiotics. Sure, it might help you feel in control of getting better, but it will make all of us more unwell in the long run.

I don’t want to sound like a broken record here, but the biggest blind spot is: you guessed it, class. While Rizvi acknowledges her own privileged upbringing as a limit to her ability to empathise, what is needed here is not an alternative individual view but rather a different analysis of how to fix a broken system. Of course proposing a workable solution requires identifying the underlying problem. If you ignore class, then you’re destined to merely tinker around with the symptoms.

Rizvi’s book is similar to Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean-In

The thing is, all our problems don’t just boil down to how we are socialised. Rizvi claims that “the challenge for each of us is to rise above our own conditioning”. But thinking about the pitch of my voice at work, or asking for a salary increase, isn’t really going to make a huge difference – except of course, for me as an individual. That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t question gender norms, but it does mean that we might have to go beyond ways of individually speaking, dressing, thinking, and acting, if we want to make substantive change.

I was a little surprised that Rizvi stayed so closely to discussing things individuals can do, given that she claims in the beginning of her book the work is “unashamedly feminist”, and also notes at the end that “it is only together that we can change the world”. These words remain, for the most part, vague gestures. I can well imagine my grandma reading this book and saying to me “we were talking about these issues in the 70s”. That’s the point isn’t it: gender inequality is a persistent problem. If you want to acknowledge the changes in our lives for the better that have occurred, you have to talk about the struggles and the tactics that have gone before.

What’s interesting here is that Rizvi and I are the same age, and we went to the same university, at the same time (and did student politics together – I was in the Labor students club that she was the leader of). Unlike Rizvi though, I came from a very poor single-parent family. Yet, we both were able to get stellar educations. Despite my low SES background, there were quite a few structural supports in place such as public housing and welfare support, as well as decent free primary and secondary schooling, that meant I could get a leg up. I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that some of these structural supports were targeted by the very Gillard government Rizvi fondly remembers working for.

What’s interesting here is that Rizvi and I are the same age, and we went to the same university, at the same time (and did student politics together – I was in the Labor students club that she was the leader of). Unlike Rizvi though, I came from a very poor single-parent family. Yet, we both were able to get stellar educations. Despite my low SES background, there were quite a few structural supports in place such as public housing and welfare support, as well as decent free primary and secondary schooling, that meant I could get a leg up. I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that some of these structural supports were targeted by the very Gillard government Rizvi fondly remembers working for.

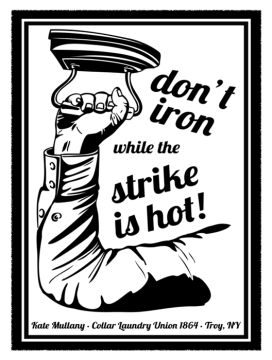

Rizvi does suggest that there are policies that need to change in order to best address gender inequality. Rizvi also makes one note about unions, and a worker’s strike in Brisbane in 1912. These pages provide a short breath of fresh air in the discussion about how to make change. But strangely Rizvi moves seamlessly from discussing the importance of joining your union, to how to treat the symptoms of an unfair system which includes how to be a great boss.

I think is somewhat of an indicator of what’s wrong with contemporary Labor politics. It’s not really about representing the working class, because the interests of bosses are seen as equally important. Rather than seeing how being in the position of boss under capitalism necessitates exploiting those below you, not attending to class at all means you can’t acknowledge nor resolve that power dynamic. Here’s the rub: CEOs and working class people do not share the same interests, even if they share the same gender identity.

Rizvi brings up Elsa quite a bit so this feels relevant

This book is explicitly inspired by the Sheryl Sandberg Lean In idea: the cruelly optimistic notion that you too can succeed, if you employ the correct tactics. But in a world that is becoming more and more unequal in terms of the distribution of wealth, where a handful of corporations own pretty much everything, and where capital and profit is valued over human and environmental well-being, success cannot be measured by how well you individually survive the fire.

Rizvi proposes that it’s not really luck but hard work that gets you ahead as a woman. We would do well to question whether the ceiling is really a class one that needs to be broken, in order to make lasting change for the lives of women at large.

Last night I was lucky enough to see Clementine Ford launch her book

Last night I was lucky enough to see Clementine Ford launch her book

However, the feminism of the 1970’s was not without its problems. Many women of colour raised important issues about what mainstream feminism was hoping to achieve – the question became: feminism is liberation for whom? Women of colour such as

However, the feminism of the 1970’s was not without its problems. Many women of colour raised important issues about what mainstream feminism was hoping to achieve – the question became: feminism is liberation for whom? Women of colour such as

I also definitely take Ford’s point that the whole “

I also definitely take Ford’s point that the whole “ In contrast to Ford’s identity politics and patriarchy theory, we could imagine a politics which attends to issues of identity, which recognises that sexism disproportionately affects people of different identities in different ways, but which doesn’t found the political moment in identity itself.

In contrast to Ford’s identity politics and patriarchy theory, we could imagine a politics which attends to issues of identity, which recognises that sexism disproportionately affects people of different identities in different ways, but which doesn’t found the political moment in identity itself.