Below is a slightly extended version of an invited plenary panel talk I gave at the Association for the Study of Australian Literature (ASAL)/Association for the Study of Literature, Environment and Culture Aus and NZ (ASLEC-ANZ) Conference, on July 6 in Melbourne, Australia. The theme of the panel was “Uncertainty’s Place”. I donated my speaker’s fee for this talk to the Trans Justice Project: you can donate here.

In my talk today I want to respond to Jennifer’s provocation in the description for this plenary about the potential crossover between reactionary voices on gender and local responses to climate change. It is my hope that in elucidating the enmeshment of these voices that we might be better placed to critique them.

On one level, the links between reactionary voices on climate and gender might seem obvious: the actors on the right who champion the fossil fuels industry, or who deny climate change altogether, champion reactionary ideas on the topic of gender. In an Australian context we don’t have to look very hard to find examples of this, or the publications that simultaneously spruik these ideologies. However, digging into the coalition of reactionary voices on gender, the picture becomes a little more confusing, the stated positions on the environment a lot more disparate. There is a spectrum of voices in this coalition. From fascists, to traditionally conservative politicians, teaming up with with those who describe themselves as left-wing, some of whom have come out of the environment movement. Is their anti-trans agenda the only thing that unites them?

The aim of this talk isn’t to detail all of the connections between the far right and anti-trans feminists, or to consider the fascist aspects of anti-trans sentiments, as others have explored. Rather, it is to take these self-proclaimed anti-trans feminists at face value (as feminists, as left-wing) to understand what is at the philosophical root of their coalitions with the right over this issue, and, what this possibly has to do with climate change.

The shared term that has been weaponised by those voices opposing gender diversity and transgender rights, is “gender ideology”. We can understand the emergence of this opposition (this “reaction”) historically against the context of the rise of a different mobilisation of feminist activists in the past decade, many of whom are intersectional feminists, and also connected to the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, as well as struggles for LGBTQ+ rights. During this period there has been increasing articulation and media visibility of transgender people and their stories and experiences. There have also been legislative wins in rights for LGBTQ+ people broadly, such as marriage equality, and also around gender recognition and birth certificate laws. In the wake of this activism, visibility, and legislative gains, there has been backlash, from right wing evangelicals and people who call themselves radical feminists (or, “gender critical feminists”) alike.

Image 4: The neo-Nazi group who turned up to support the “Let Women Speak” rally in Melbourne 2023

In its most right wing and fascistic formations, backlash has focused on so-called “gender ideology” as threat to the nuclear family and thereby the Nation state. For example, in 2017, far-right Christian protestors gathered in Sao Paulo to protest pre-eminent gender studies scholar Judith Butler’s appearance at a local conference, calling them a witch, burning an effigy of them, and claiming that they were out to corrupt the sexual identities of children.

As Butler reflected on this protest: “My sense is that the group who engaged this frenzy of effigy burning, stalking and harassment want to defend ‘Brazil’ as a place where LGBTQ people are not welcome, where the family remains heterosexual (so no gay marriage), where abortion is illegal and reproductive freedom does not exist. They want boys to be boys, and girls to be girls, and for there to be no complexity in questions such as these. The effort is antifeminist, antitrans, homophobic and nationalist, using social media to stage and disseminate their events. In this way, they resemble the forms of neo-fascism that we see emerging in different parts of the world.” We have also seen this fascistic element more locally, in the streets of Melbourne when neo-Nazis turned up to the Let Women Speak rally in March this year.

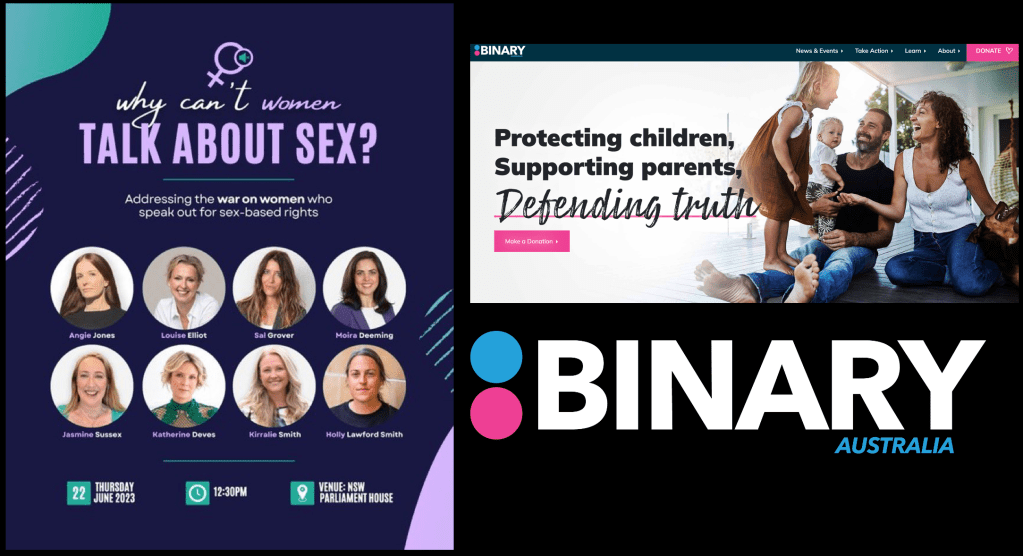

Right: The Binary Australia website header and logo

What we have here is essentially is a coalition of seemingly unlikely allies who are all focused on opposing rights for transgender people. Some are explicitly fascist groups. Some are conservative politicians, often evangelical. Yet some describe themselves as feminists, usually “gender critical” feminists. So, for example in June a talk was held at NSW Parliament House called “Why can’t women talk about sex?”. Speakers included a mix of conservative politicians (e.g. Louise Elliot), activists (e.g. Sal Grover, Katherine Deves), and self-described “gender critical” feminist academic Holly Lawford Smith. It was hosted by a Liberal Democrat MP and also attended by Liberal and Labor MPs. It was broadcast by a new right-wing independent digital media company called ADH TV, and promoted via Binary Australia, the group who ran the “No” campaign against marriage equality in Australia in 2017 and subsequently rebranded to focus on anti-trans issues.

Here, anti-trans activism is the hinge. When it comes to climate change and environmental issues generally within these coalitions, there is divergence. Broadly, some of those actors are climate change sceptics, others acknowledge climate change and argue for nuclear as the solution, and when it comes to the people identifying as radical or “gender critical” feminists some of them are nominally environmental activists, or have come from this movement. So for example, we have conservative Katherine Deves, who unsuccessfully ran for the Liberal party in the 2022 Federal election, who occasionally tweets about nuclear power, and indeed this issue is at the heart of Liberal party debates happening this week at the National convention. Conversely, before pivoting seemingly inexplicably to anti-trans philosophy, Holly Lawford Smith was an environmental philosopher who wrote about the moral duty of individuals to act on climate change. However, tellingly, in Lawford Smith’s 2022 book “Gender Critical Feminism”, she outlines,

“[All things] relating centrally to women’s reproductive role and gender expectations applied on the basis of her being female, will be on the feminist agenda as we’ve outlined it. But climate justice won’t be. Climate justice is an everyone issue, not a feminist issue. And that’s a good thing, because as I have been arguing, when it becomes feminism’s job to smash capitalism and fight climate change there’s a serious risk that feminism simply becomes debilitated by being stretched too thinly, by having too much asked of it” (Lawford Smith, 2022, p.159, emphasis in original). As she also reflects, “Nothing has ever seized my attention and refused to relax its grip like [gender critical] feminism has. I have cared about social justice issues, most significantly in recent years climate justice, but I have never been consumed by them” (Lawford Smith, 2022, p.208).

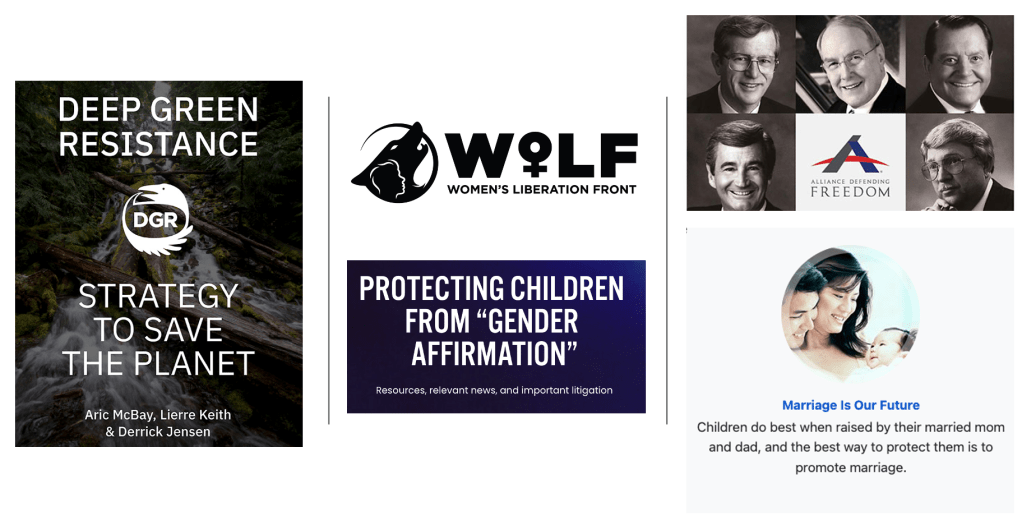

Image 2: The logo for the Women’s Liberation Front (WoLF) and an example from one of their campaigns

Image 3: An image of the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF) and an example from one of their campaigns

I want to give one more strange, telling, example of these coalitions in the USA context, before getting to my point. In 2011 Lierre Keith, co-founded the group “Deep Green Resistance front” (DGR), a direct-action group which calls for a “world without industrial civilization” for the benefit of the environment. As their website describes, “When civilization ends, the living world will rejoice. We must be biophilic people in order to survive”. DGR also describes itself as a “radical feminist organisation” and in its statement of principles includes “Gender is not natural, not a choice, and not a feeling: it is the structure of women’s oppression. Attempts to create more ‘choices’ within the sex-caste system only serve to reinforce the brutal realities of male power”. While DGR seems to have fractured over this issue, in 2013 Lierre created another group, the Women’s Liberation Front (WoLF). WoLF organises predominately around anti-trans issues with a stated focus on “abolishing gender ideology”. Despite being nominally in favour of abortion rights, WoLF has received funding from the conservative Christian group Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF) and have co-organised rallies in the USA against trans rights. ADF’s main focus is on ending access to abortion and winding back rights for LGBTQ+ people in the USA.

As C. Libby (2022) explains in their analysis of the links between evangelicals and trans-exclusionary feminists, “Despite their distinct historical and ideological lineages, contemporary evangelical and trans-exclusionary radical feminist positions on transgender issues share an affective resonance… Anti-trans rhetoric today positions transgender rights as part of a larger ‘transgender agenda’ that threatens to endanger women and children and to strip Christians of their civil rights” (Libby, 2022, p.429).

Rather than thinking about these alliances as simply opportunistic coalitions meeting on anti-trans rights, there is something fundamentally shared at the basis of these positions. As we readily see in the WoLF and ADF examples, children are often placed at the centre of their campaigns, as the basis upon which the fight is mounted. My claim is, that what is being conceptually weaponised here, what is fundamentally being fought over is not the present moment, but rather, the future. We can productively turn to queer theorist Lee Edelman (2004) here, who describes how the figure of the Child is often wielded in politics and culture as a symbol of the future, and specifically a future that is founded in the (white) heterosexual nuclear family. Edelman shows how children are symbolically connected to life and reproductive futurity, while queer people are marked as representing death and “no future”.

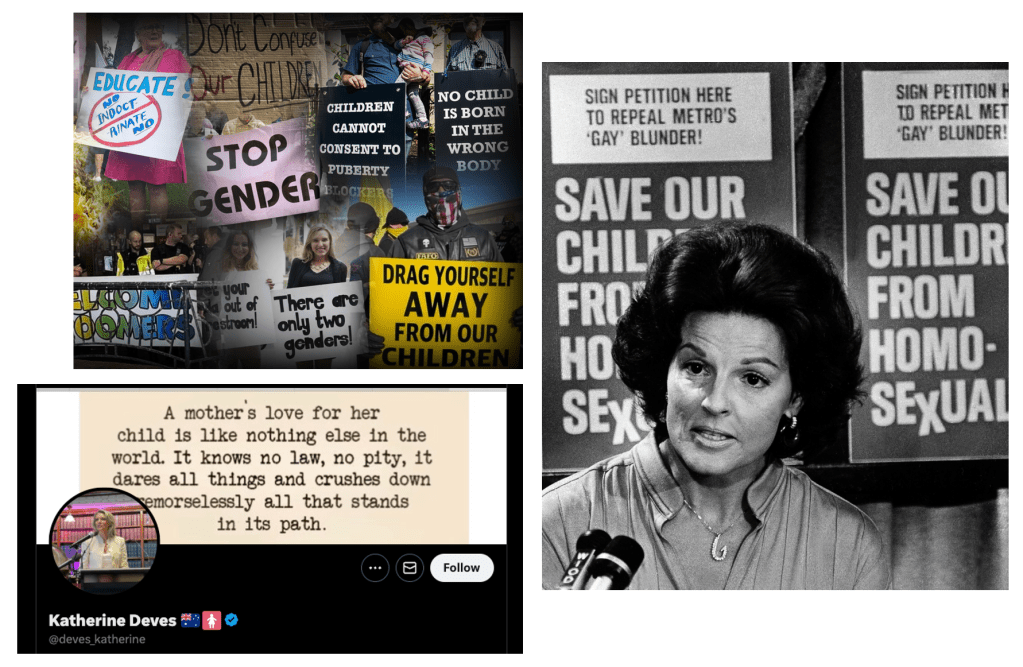

Image 2: Katherine Deves’ Twitter header which reads “A mother’s love for her child is like nothing else in the world. It knows no law, no pity, it dares all things and crushes down remorselessly [on] all that stands in its path”

Image 3: Anita Bryant (the original Posie Parker) campaigning against gay civil rights in the 1960s

We see this playing out today with constant fearmongering around the impact of “gender ideology” on children. We see this in “gender critical” calls to “save the tomboy”, to “stop child transition”, and to preserve conversion therapy practices. We see this in the fascist protests that invoke pedophilia and use images of children being “harmed” by “gender ideology”, and at their protests of drag queen story time events at libraries. We see this in the propaganda of sites like Binary Australia, who state their key aim as “protecting children”. We even see this in the social media profiles of failed politicians like Katherine Deves who paints a vivid vision of violence in the name of children. Incredibly much of the language of these protests directly invokes old “save our children” rhetoric seen for example in the USA in the 1960s, with organised campaigns against gay civil rights.

Yet, departing from Edelman what I’d like to point out is that we are seeing in Australia is not just the invocation of the child as the symbol of the future but the white “female” body as the carrier of that child as under threat. Much of this constructs the category of “mother” as the supreme moral arbiter of what is good and right, what is “common sense”. So for example, this piece published by Binary Australia uses the language of the stolen generation of Indigenous children in Australia’s history, washing this of its specific racist history and transposing it onto fear about “gender ideology” as “the stolen genderation”, depicting a white hand against a fence and penned by “A. Mother”. In using this title and image, what is called to mind is a kind of white genocide. When we look at the content of these articles, speeches from conservative politicians, and books by “gender criticals” what we see is a framing of women and children under immense threat: women’s bodies as being “colonised” and “erased”, and sex as being “eliminated”. While these actors may share nominally different positions on climate change, what is shared is a displacement of fear and uncertainty about the future, that is threatened by the shadow of climate change, onto a threat against children and women, with the solution founded in the presumed certainty, materiality, of the sexed body.

Relief from climate apocalypse comes in the name of fabricating a different threat, a war against culture (“gender ideology”) over nature (the sexed body, specifically white cisgender women’s bodies).

As Sophie Lewis and Asa Seresin argue in their (2022) article on the connection between fascism and feminism in today’s anti-trans activism, the view of anti-trans activists amounts to “…an extinction fantasy narrative” or “apocalyptic intoxication”. As Lewis suggests: “I suppose what I am claiming is that the millenarian emergency of ‘female erasure’ imagined by Mary Daly, Sheila Jeffreys, and Janice Raymond is an imminent disaster the cisterhood loves, Cassandra-like, to hate” (p.470). Very similarly Libby (2022) highlights how evangelical pamphlets condemning transgender subjectivity stress “moral decay, contagion, and apocalypticism” (2022, p.426).

The reactionary voices in question are fighting for a construction of the future that is certain: where “boys are boys” and “girls are girls”, where this is founded in a biological guarantee, imagined as a concrete and immutable reality. In the meantime, the status quo can continue without having to challenge the logics of capitalist industrial growth, consumption, or emissions. This is not just the logical consequence of the politics of conservative actors in this coalition against “gender ideology”. In constructing “gender critical” feminism as a “single axis” politics that rejects so-called “burdens” of other axes such as race and class, or concerns like environmentalism (Lawford Smith, 2022, p.58), it cannot help but leave a vacuum for its coalition partners to fill on other issues, precisely because it is purportedly concerned with nothing other than “sex”. Vitally, it promotes climate inaction because they are too focused on fighting a confected culture war. Disaffection, defeatism, and opportunism come together to spectacularly imagine a whole new threat.

Crucially, as Gayle Rubin wrote in 1982, when the fear was nuclear war and the battle was the so-called feminist “sex wars” over pornography and kink, “…it is precisely at times such as these, when we live with the possibility of unthinkable destruction, that people are likely to become dangerously crazy about sexuality… Disputes over sexual behaviour often become the vehicles for displacing social anxieties, and discharging their attendant emotional intensity” (p.137-138). Though in this case now it is gender, “gender ideology” is suffused with a sense of the sexual order under threat. Why sexuality? Because when the future is imperilled – as it is now, with the very real apocalypse of climate change looming overhead – reproduction, imagined as the future of the species, becomes an easy latch, a more manageable apocalypse.

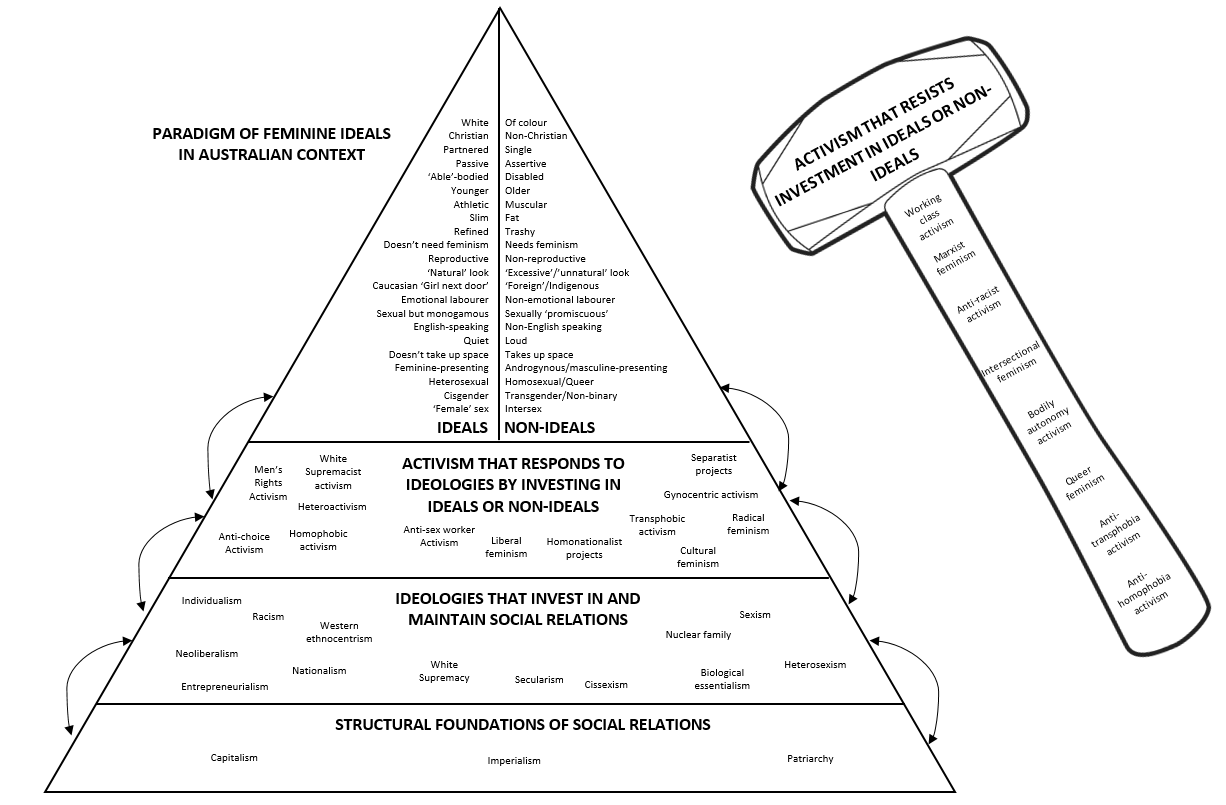

I like to think in visual terms, and the diagram above (click on it to enlarge) is an attempt to sum up how we might connect structure, activism, and norms in a useful way. I’ve included a hammer here as a kind of nuanced update to that “If I had a hammer” image.

I like to think in visual terms, and the diagram above (click on it to enlarge) is an attempt to sum up how we might connect structure, activism, and norms in a useful way. I’ve included a hammer here as a kind of nuanced update to that “If I had a hammer” image. At the very base are the “structural foundations”, which accounts for the economic, colonial, and gendered power structures that are the foundation of the dominant organisation of social relations in this context. Flowing from this foundation, but also feeding back into it, are the dominant ideologies that invest in and maintain these social relations. For example, neoliberalism is an ideology that supports capitalism. Similarly White supremacy is an ideology that supports imperialism. Flowing from this, there are various forms of activism that respond to these ideologies in ways that either bolster these ideologies or reject them. The activism that bolsters these ideologies also works toward cementing what is understood as the “ideals”.

At the very base are the “structural foundations”, which accounts for the economic, colonial, and gendered power structures that are the foundation of the dominant organisation of social relations in this context. Flowing from this foundation, but also feeding back into it, are the dominant ideologies that invest in and maintain these social relations. For example, neoliberalism is an ideology that supports capitalism. Similarly White supremacy is an ideology that supports imperialism. Flowing from this, there are various forms of activism that respond to these ideologies in ways that either bolster these ideologies or reject them. The activism that bolsters these ideologies also works toward cementing what is understood as the “ideals”. It is clear for example, that

It is clear for example, that  Perhaps this is what might mark out a new wave of (feminist and other) activism around femininity: challenging gender ideals without investing in non-ideals as the political response. From such a perspective, there is no femininity that is “empowered”. Power is exerted and ideals are enforced, but the reaction to this is to focus on the structural foundations and their ideological props rather than the individual effects alone (which might for some involve complicated attachments).

Perhaps this is what might mark out a new wave of (feminist and other) activism around femininity: challenging gender ideals without investing in non-ideals as the political response. From such a perspective, there is no femininity that is “empowered”. Power is exerted and ideals are enforced, but the reaction to this is to focus on the structural foundations and their ideological props rather than the individual effects alone (which might for some involve complicated attachments). For

For  In her article, Freeman praises recent protests against the

In her article, Freeman praises recent protests against the  I was shocked that The Guardian would run this on

I was shocked that The Guardian would run this on  Luckily, changes to the GRA would reduce the clinical barriers needed to have gender identity recognised, which would mean less stress and burden for trans people and would reduce some of the pathologising elements of the process. If gender was truly liberated, we wouldn’t need to diagnose what expressions of gender are “normal”, we would celebrate a diversity of expressions, embodiments and feelings.

Luckily, changes to the GRA would reduce the clinical barriers needed to have gender identity recognised, which would mean less stress and burden for trans people and would reduce some of the pathologising elements of the process. If gender was truly liberated, we wouldn’t need to diagnose what expressions of gender are “normal”, we would celebrate a diversity of expressions, embodiments and feelings. As

As  Freeman claims that there is a massive issue with trans feminists who critique the centring of reproductive systems. She states, “I’m trying to think of anything more patriarchal than telling women to stop fussing about vaginas at a Women’s March”. What Freeman misses is that the issue isn’t talking about bodies and the material experience of gender altogether, the problem is creating a reductive version of feminism where vagina = woman and where this is made into the central focus of collective action. This doesn’t mean we can’t talk about issues like abortion, pregnancy, or periods either (all issues which affect a range of gendered peoples), it just means that we shouldn’t make biology the basis for our collective resistance.

Freeman claims that there is a massive issue with trans feminists who critique the centring of reproductive systems. She states, “I’m trying to think of anything more patriarchal than telling women to stop fussing about vaginas at a Women’s March”. What Freeman misses is that the issue isn’t talking about bodies and the material experience of gender altogether, the problem is creating a reductive version of feminism where vagina = woman and where this is made into the central focus of collective action. This doesn’t mean we can’t talk about issues like abortion, pregnancy, or periods either (all issues which affect a range of gendered peoples), it just means that we shouldn’t make biology the basis for our collective resistance. The claim that somehow “predatory men” will be emboldened to “come into female-only spaces unchallenged” is a transphobic furphy that’s been trotted out by right wing commentators for a long time now, and that has been

The claim that somehow “predatory men” will be emboldened to “come into female-only spaces unchallenged” is a transphobic furphy that’s been trotted out by right wing commentators for a long time now, and that has been  If all of this seems pretty basic, it’s because it is. Fundamentally it doesn’t matter what the relationship between biology (“sex”) and identity (“gender”) is, what really matters is treating human beings with dignity and celebrating the possibilities of gender. Because loosening the rules of gender, understanding gender and sexism beyond biology, talking about body issues but not reducing people to bodies, and thinking about how to have solidarity around the lived experiences of gender, should be fundamental to feminism. The alternative – the world that Freeman seeks to enforce – is not only a trans-exclusionary, it works against what decades of feminists have been fighting for.

If all of this seems pretty basic, it’s because it is. Fundamentally it doesn’t matter what the relationship between biology (“sex”) and identity (“gender”) is, what really matters is treating human beings with dignity and celebrating the possibilities of gender. Because loosening the rules of gender, understanding gender and sexism beyond biology, talking about body issues but not reducing people to bodies, and thinking about how to have solidarity around the lived experiences of gender, should be fundamental to feminism. The alternative – the world that Freeman seeks to enforce – is not only a trans-exclusionary, it works against what decades of feminists have been fighting for. Jamila Rizvi’s recently released book

Jamila Rizvi’s recently released book

What’s interesting here is that Rizvi and I are the same age, and we went to the same university, at the same time (and did student politics together – I was in the Labor students club that she was the leader of). Unlike Rizvi though, I came from a very poor single-parent family. Yet, we both were able to get stellar educations. Despite my low SES background, there were quite a few structural supports in place such as public housing and welfare support, as well as decent free primary and secondary schooling, that meant I could get a leg up. I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that some of these structural supports

What’s interesting here is that Rizvi and I are the same age, and we went to the same university, at the same time (and did student politics together – I was in the Labor students club that she was the leader of). Unlike Rizvi though, I came from a very poor single-parent family. Yet, we both were able to get stellar educations. Despite my low SES background, there were quite a few structural supports in place such as public housing and welfare support, as well as decent free primary and secondary schooling, that meant I could get a leg up. I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that some of these structural supports

The first is from trans-exclusionary radical feminist types, who conflate gay male culture with drag queens with transgender identity. Such perspectives see gay men, drag queens, and trans women as responsible for propping up fantasies of femininity that only serve to oppress women. Germaine Greer famously stated in The Female Eunuch 1970: “I’m sick of being a transvestite. I refuse to be a female impersonator. I am a woman, not a castrate”. Greer’s suggestion here is that there is some form of “natural” womanhood that can be liberated from the dictates of culture. Similarly, and more recently, Sheila Jeffreys has even argued that drag kings distort lesbian culture and the celebration of “natural” womanhood. She writes: “If the suffering and destruction of lesbians is to be halted then we must challenge the cult of masculinity that is evident in such activities as drag king shows”. These views are rife with homophobia and transphobia, as well as massive conflations and wild leaps that see men, masculinity, and femininity, as the true oppressors of women.

The first is from trans-exclusionary radical feminist types, who conflate gay male culture with drag queens with transgender identity. Such perspectives see gay men, drag queens, and trans women as responsible for propping up fantasies of femininity that only serve to oppress women. Germaine Greer famously stated in The Female Eunuch 1970: “I’m sick of being a transvestite. I refuse to be a female impersonator. I am a woman, not a castrate”. Greer’s suggestion here is that there is some form of “natural” womanhood that can be liberated from the dictates of culture. Similarly, and more recently, Sheila Jeffreys has even argued that drag kings distort lesbian culture and the celebration of “natural” womanhood. She writes: “If the suffering and destruction of lesbians is to be halted then we must challenge the cult of masculinity that is evident in such activities as drag king shows”. These views are rife with homophobia and transphobia, as well as massive conflations and wild leaps that see men, masculinity, and femininity, as the true oppressors of women. I don’t have much time for these views, which encourage us to believe that the biggest threats to women are trans women, drag queens, and gay men. This view distorts Marxist theory to argues that men in particular are *the* class that oppresses women, and sees the liberation that is to be won as a liberation from “gender”. Luckily the currency of radical feminism in academic spaces seems to be waning. But when overall activist struggle in society is low, it is easy for people to slip into arguing that we are each other’s problem, that if only we could free ourselves from gender we’d be truly liberated. It’s a much easier argument to make than organising to transform the fundamental economic arrangement of society, and it makes space for all kinds of class collaboration between powerful women and poor women alike (even if it means at the end of the day that power doesn’t actually shift).

I don’t have much time for these views, which encourage us to believe that the biggest threats to women are trans women, drag queens, and gay men. This view distorts Marxist theory to argues that men in particular are *the* class that oppresses women, and sees the liberation that is to be won as a liberation from “gender”. Luckily the currency of radical feminism in academic spaces seems to be waning. But when overall activist struggle in society is low, it is easy for people to slip into arguing that we are each other’s problem, that if only we could free ourselves from gender we’d be truly liberated. It’s a much easier argument to make than organising to transform the fundamental economic arrangement of society, and it makes space for all kinds of class collaboration between powerful women and poor women alike (even if it means at the end of the day that power doesn’t actually shift).

So that’s why it’s kind of surprising to hear people within queer communities suggesting now that drag, in its mainstream formations, is a problem. From this perspective drag, if performed by ostensibly

So that’s why it’s kind of surprising to hear people within queer communities suggesting now that drag, in its mainstream formations, is a problem. From this perspective drag, if performed by ostensibly