Recently an article, Dark Undercurrents of Teenage Girls’ Selfies, has been doing the social media rounds. Selfie literally refers to taking a photo of yourself, and as the papers would have it, this is a dangerous trend being taken up predominantly by girls. While the author – a grade eleven student – admits that “There isn’t anything inherently wrong with uploading self-portraits”, part of this piece also claims that the underlying motivation is popularity, ultimately judged by men:

Who do we blame for this moral mess? As feminists, we correctly blame patriarchy because boys are securely at the top of the status game. Boys end up with the authority. They have their cake and eat it.

On the weekend The Observer also jumped on the bandwagon with an ominous appraisal over this “global phenomenon”. Journalist Elizabeth Day argues that even though the selfie allows for a modicum of control over images, “once they are online, you can never control how other people see you”. And as Anna Goldsworthy recently remarked in her piece for the Quarterly Essay:

And so the young woman photographs herself repeatedly, both in and out of her clothes, striking the known poses of desire: the lips slightly parted, the “come hither” eyes, the arched back or cupped breast.

By all accounts, young girls today are not just in big trouble, they are trouble. Unlike every generation before them, these girls are the lewdest, excessively raunchy, most aggressively hypersexual… What we have on our hands is a moral panic that combines two things we love to fret about: technology and women’s bodies.

By all accounts, young girls today are not just in big trouble, they are trouble. Unlike every generation before them, these girls are the lewdest, excessively raunchy, most aggressively hypersexual… What we have on our hands is a moral panic that combines two things we love to fret about: technology and women’s bodies.

I think that whether or not selfies are ultimately empowering vs. disempowering is actually a moot point. After all, this line of questioning can only really disseminate along two opposing lines:

- Empowering – Girls are in control, and the elements of choice and agency involved in self-constructing images is key. This perspective necessitates extrapolating individual claims out to the whole.

- Disempowering – Girls may think they have control when they produce a selfie but really as outsiders we know better: they are the victims of a patriarchal culture that compels them to auto-objectivise. This perspective necessitates making generalisable structural claims to the detriment of considering individual experience.

Both of these lines of argument involve making wide-spread claims to provide a definitive evaluation that the practice of taking selfies is either good or bad. From this black and white approach, the possibility that something might be at once empowering and disempowering, is obscured. But – let’s take an imaginative leap here – what if we decided that actually, the answer to the empowerment question is actually kind of fuzzy…

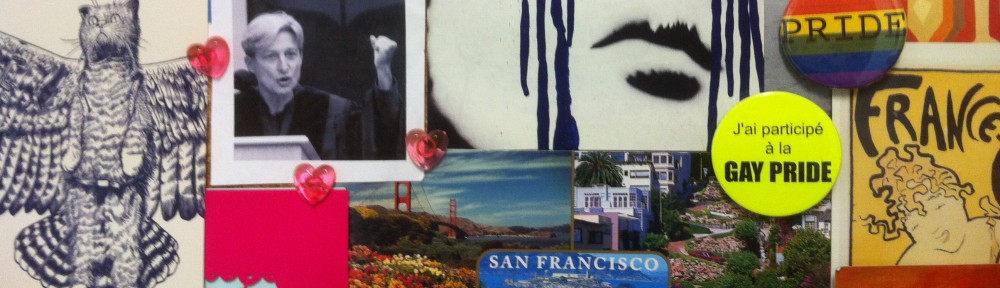

It is almost certain that, as Olympia Nelson claims, many young people are playing popularity games through selfie posts. But what if we considered the ways in which online environments are opening up new avenues for exploration of identity and selfhood? Capacitating the formation of new communities? Creating space for young people to experiment with different modes of self-expression? Selfies are just one more form of image being produced and reproduced in this world. But why flatten girlhood through this story of the scourge of selfie, and miss the other aspects at play in this question of growing up in an era where online expression is the norm?

Nelson herself admits that “The real problem relates to conformity” – but unfortunately her morality-tale (clearly sensationalised by the paper, e.g. the byline “a cut-throat sexual rat race”) doesn’t leave room for a more in-depth look at how she herself engages online aside from her general, mostly generalised, examples. It seems to me that there are more interesting questions to ask about being a young person on social media if we can put aside our immediate reactions, dry our sweaty brows for a minute and calm our anxiety over the “youth of today”.

The point is, why not suspend judgement and condemnation of these girls and their online practices? Let’s think of some new ways to engage with questions of technology, sexuality and gendered bodies…without all the panic.