The confected “debate” about the legitimacy of trans lives does not seem to be going away, and indeed is becoming a key feature of the culture wars in Australia and abroad. In recent years a small group of activists have rebranded themselves “Gender Critical (GC) Feminists” (distancing themselves from the term “Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist (TERF)”, which they claim is a slur). Despite being marginal in their views around trans rights, GC activists continue to receive a huge amount of media attention and platforming, often in the conservative press (but sometimes also, sadly, in outlets such as The Guardian and The Conversation). Many GC activists also continue to hold senior positions in the academy, which adds legitimacy to their public commentary, despite the fact that very few of them have any expertise in gender studies and many have no peer reviewed publications on trans issues.

When we delve into the arguments of GC activists many outright deny the legitimate existence of trans people altogether, claiming, for example, that “our problem is with male people claiming to be women, regardless of how they present”. GC activists then must be understood not simply as “trans-exclusionary”, but as trans deniers.

It is absolutely crucial that media outlets and universities begin to recognise that like climate denial, trans denial is based on unscientific views that are wildly out of step with peer-reviewed scholarship. When GC activists suggest that trans rights ought to be “debated” on the basis of “free speech”, they set the terms of a highly uneven debate between their ideological perspectives vs. actual scholarship. If we focus on the actual scholarship, we see that there are many debates to be had in trans studies around identity, embodiment, race, decolonisation, the relation to non-binary identity, research methods, and more, but those discussions are completely annihilated by GC feminists suggesting that the debate should be about the very legitimacy of trans people in the first place.

In response to this outrageous and fabricated debate, I present (below) a very short introductory list of peer-reviewed scholarship in the field of trans studies that might be used to rebut the entirely unsupported claims of GC feminists, to illuminate the vast depths of the field of trans studies, and to illustrate to the media and universities alike that the “debates” are to be found elsewhere from where GC feminists claim. This is by no means an exhaustive list – there are literally thousands of articles on trans studies, and more are published each day. (There is, of course, much amazing writing published by trans people outside of the academy, my point here though being that trans studies is a huge field of academic scholarship, a point mostly overlooked in public “debates”).

If you would like to view/download a copy of this list please click here. If you think something should be added to this short list of peer-reviewed scholarship (or removed) please contact me.

Journals/special issues and key texts/readers (rebuttal to claims of “trans orthodoxy” – trans studies is not mere political polemics, it is an established and legitimate field of study)

TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly https://read.dukeupress.edu/tsq

International Journal of Transgender Health https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/wijt21/current

Women’s Studies Quarterly (2008) 36(3/4) Special Issue on ‘Trans-’ edited by P. Currah, L. J. Moore & S. Stryker https://www.jstor.org/stable/i27649777

GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies (1998) 4(2) Special Issue on ‘The Transgender Issue’ edited by S. Stryker https://read.dukeupress.edu/glq/issue/4/2

Hypatia (2009) 24(3) Special Issue on ‘Transgender Studies and Feminism: Theory, Politics, and Gendered Realities’ edited by T.M. Bettcher & A. Garry https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/15272001/2009/24/3

Gender, Place & Culture (2010) 17(5) Special theme on ‘Trans Geographies’ edited by K. Browne, C. J. Nash & S. Hines https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2010.503104

TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly (2014) 1(3) Special Issue on ‘Decolonizing the Transgender Imaginary’ edited by A. Aizura, M. Ochoa, S. Vidal-Ortiz, T. Cotton, C. Balzer/C. LaGata https://www.dukeupress.edu/decolonizing-the-transgender-imaginary-1

S. Stryker & S. Whittle (eds) (2006) The Transgender Studies Reader. London: Routledge https://www.routledge.com/The-Transgender-Studies-Reader/Stryker-Whittle/p/book/9780415947091

S. Stryker & A.Z. Aizura (2013) The Transgender Studies Reader 2. New York: Routledge https://www.routledge.com/The-Transgender-Studies-Reader-2/Stryker-Aizura/p/book/9780415517737

A. Haefele-Thomas (2019) Introduction to Transgender Studies. Columbia University Press http://cup.columbia.edu/book/introduction-to-transgender-studies/9781939594273

S. Hines & T. Sanger (eds) (2010) Transgender identities: Towards a social analysis of gender diversity. New York: Routledge https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/37306

D. Spade (2015) Normal life: Administrative violence, critical trans politics, & the limits of law. Durham, NC: Duke University Press http://www.deanspade.net/books/normal-life/

G. Salamon (2010) Assuming a Body: Transgender and Rhetorics of Materiality. Columbia University Press http://cup.columbia.edu/book/assuming-a-body/9780231149587

J. Halberstam (2018) Trans: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability. University of California Press https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520292697/trans

J. Serano (2007) Whipping Girl: Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity. Emeryville, CA: Seal Press https://www.sealpress.com/titles/julia-serano/whipping-girl/9781580056229/

K. Bornstein and S. Bear Bergman (eds) (2010) Gender outlaws: the next generation. Berkeley: Seal Press https://www.sealpress.com/titles/kate-bornstein/gender-outlaws/9781580053778/

C. Richards, W.P. Bouman & M-J. Barker (eds) (2017) Genderqueer and Non-Binary Genders. London: Palgrave Macmillan https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9781137510525

Trans theory and history (rebuttal to the claim that trans is an entirely ‘new’ concept – while some terms have changed over time, trans theory continues to grow and change)

S. Stryker (2017). Transgender History, Second Edition: The Roots of Today’s Revolution. Berkeley: Seal Press https://www.sealpress.com/titles/susan-stryker/transgender-history-second-edition/9781580056908/

S. Stone ([1987] 2006) ‘The empire strikes back: A posttranssexual manifesto’. In The transgender studies reader, Susan Stryker & Stephen Whittle (eds). New York: Routledge https://uberty.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/trans-manifesto.pdf

J. Prosser (1998) Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality. New York: Columbia University Press http://cup.columbia.edu/book/second-skins/9780231109345

T. Ellison, K. M. Green, M. Richardson, C. Riley Snorton (2017) ‘We Got Issues: Toward a Black Trans*/Studies’, TSQ, 4(2): 162–169 https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-3814949

S. Stryker (2004) ‘Transgender Studies: Queer Theory’s Evil Twin’, GLQ, 10(2): 212–215 https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-10-2-212

J. Halberstam (2005) In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York: New York University Press https://nyupress.org/9780814735855/in-a-queer-time-and-place/

L. Feinberg (1998) Trans liberation: beyond pink or blue. Boston: Beacon Press https://www.worldcat.org/title/trans-liberation-beyond-pink-or-blue/oclc/607065169

S. Stryker (2008) ‘Transgender History, Homonormativity, and Disciplinarity’, Radical History Review, (100): 145–157 https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-2007-026

P. Califia (1997) Sex changes: the politics of transgenderism. San Francisco: Cleis Press https://www.worldcat.org/title/sex-changes-the-politics-of-transgenderism/oclc/36824894

V. K. Namaste (2000) Invisible lives: The erasures of transsexual and transgendered people. Chicago: University of Chicago Press https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/I/bo3683192

C. M. Keegan (2020) ‘Getting Disciplined: What’s Trans* About Queer Studies Now?’, Journal of Homosexuality, 67(3): 384-397 https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1530885

C. Adair, C. Awkward-Rich & A. Marvin (2020) ‘Before Trans Studies’, TSQ, 7(3): 306-320 https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-8552922

M. Day (2020) ‘Indigenist Origins: Institutionalizing Indigenous Queer and Trans Studies in Australia’, TSQ, 7(3): 367–373 https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-8553006

Transfeminist approaches (rebuttal to the claim that feminism and trans studies are incompatible – these texts look at the tensions between feminist and trans studies from transfeminist perspectives)

A. F. Enke (Ed.) (2012) Transfeminist perspectives: In and beyond transgender and gender studies, Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt14bt8sf

E. Koyama ([2000] 2020) ‘Whose feminism is it anyway? The unspoken racism of the trans inclusion debate’, The Sociological Review, 68(4): 735-744, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120934685

V. Varun Chaudhry (2020) ‘On Trans Dissemblance: Or, Why Trans Studies Needs Black Feminism’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 45(3): 529-535 https://doi.org/10.1086/706466

M. Nanney & D.L. Brunsma (2017) ‘Moving Beyond Cis-terhood: Determining Gender through Transgender Admittance Policies at U.S. Women’s Colleges’, Gender & Society, 31(2): 145-170 https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243217690100

S. Stryker (2007) ‘Transgender Feminism’. In S. Gillis, G. Howie & R. Munford (eds) Third Wave Feminism. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230593664_5

V. Namaste (2009) ‘Undoing theory: The “transgender question” and the epistemic violence of Anglo-American feminist theory’, Hypatia, 24(3): 11–32 https://www.jstor.org/stable/20618162

C. Heyes (2003) ‘Feminist solidarity after queer theory: The case of transgender’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28 (4): 1093–120 https://doi.org/10.1086/343132

C. Awkward-Rich (2017) ‘Trans, Feminism: Or, Reading like a Depressed Transsexual’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 42(4): 819-841 https://doi.org/10.1086/690914

A. Tudor (2019) ‘Im/possibilities of refusing and choosing gender’, Feminist Theory, 20(4): 361-380 https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700119870640

S. Hines (2019) ‘The feminist frontier: on trans and feminism’, Journal of Gender Studies, 28(2): 145-157 https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2017.1411791

Trans harassment, discrimination, erasure, surveillance (rebuttal to the claim that trans people are villains/perpetrators rather than a highly surveilled and persecuted minority – these texts provide empirical evidence and analysis of the issues faced by trans people and communities)

T. Beauchamp (2019) Going Stealth: Transgender Politics and U.S. Surveillance Practices. Durham: Duke University Press https://www.dukeupress.edu/going-stealth

B. Colliver & A. Coyle (2020) ‘“Risk of sexual violence against women and girls” in the construction of “gender-neutral toilets”: a discourse analysis of comments on YouTube videos’, Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 4(3): 359-376(18), https://doi.org/10.1332/239868020X15894511554617

K. Bender-Baird (2016) ‘Peeing under surveillance: bathrooms, gender policing, and hate violence’, Gender, Place & Culture, 23(7): 983-988 https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2015.1073699

J. James (2021) ‘Refusing abjection: transphobia and trans youth survivance’, Feminist Theory, 22(1): 109-128 https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700120974896

C.L. Quinan (2017) ‘Gender (In)Securities: Surveillance and Transgender Bodies in a Post-9/11 Era of Neoliberalism’. In M. Leese & S. Wittendorp (eds), Security/Mobility Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 153-169 https://www.manchesteropenhive.com/view/9781526108364/9781526108364.xml

A. Lubitow, JD. Carathers, M. Kelly & M. Abelson (2017) ‘Transmobilities: mobility, harassment, and violence experienced by transgender and gender nonconforming public transit riders in Portland, Oregon’, Gender, Place & Culture, 24(10): 1398-1418, https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1382451

K. Kraschel (2012) ‘Trans-cending space in women’s only spaces: Title IX cannot be the basis for exclusion’, Harvard Journal of Law and Gender, 35: 463-85 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2138896

T. Spence‐Mitchell (2021) ‘Restroom restrictions: How race and sexuality have affected bathroom legislation’, Gender Work Organisation https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12545

M. A. Case (2019) ‘Trans Formations in the Vatican’s War on “Gender Ideology”’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 44:3, 639-664 https://doi.org/10.1086/701498

R. Rosenberg & N. Oswin (2015) ‘Trans embodiment in carceral space: hypermasculinity and the US prison industrial complex’, Gender, Place & Culture, 22(9): 1269-1286 https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2014.969685

P. L. Doan (2010) ‘The tyranny of gendered spaces – reflections from beyond the gender dichotomy’, Gender, Place & Culture, 17(5): 635-654 https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2010.503121

C.L. Quinan, D. Cooper, V. Molitor, A. Kondakov, A. van der Vleuten & T. Zimenkova (2020) ‘“State Regimes of Gender: Legal Aspects of Gender Identity Registration, Trans-Relevant Policies and Quality of LGBTIQ Lives”: A Roundtable Discussion’, International Journal of Gender, Sexuality and Law, 1 (1): 377-402 https://doi.org/10.19164/ijgsl.v1i1.985

D. Irving (2015) ‘Performance Anxieties: Trans Women’s Un(der)-employment Experiences in Post-Fordist Society’, Australian Feminist Studies, 30(83): 50-64 https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2014.99845

Negotiating trans identity/lived experience (rebuttal to the claim that trans identity is not legitimate – despite attempts at erasure, trans people continue to exist and resist)

A. Rooke (2010) T’rans youth, science and art: creating (trans) gendered space’, Gender, Place & Culture, 17(5): 655-672 https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2010.503124

T.J. Jourian, S.L. Simmons, K.C. Devaney (2015) ‘“We Are Not Expected”: Trans* Educators (Re)Claiming Space and Voice in Higher Education and Student Affairs’, TSQ, 2(3): 431–446 https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2926410

S. Hines (2010) ‘Queerly situated? Exploring negotiations of trans queer subjectivities at work and within community spaces in the UK’, Gender, Place & Culture, 17(5): 597-613 https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2010.503116

I. Linander, I. Goicolea, E. Alm, A. Hammarström & L. Harryson (2019) ‘(Un)safe spaces, affective labour and perceived health among people with trans experiences living in Sweden’, Culture, Health & Sexuality, 21(8): 914-928, https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2018.1527038

A. Gorman-Murray, S. McKinnon, D. Dominey-Howes, C. J. Nash & R.Bolton (2018) ‘Listening and learning: giving voice to trans experiences of disasters’, Gender, Place & Culture, 25(2): 166-187 https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1334632

S. Hines (2007) ‘(Trans)Forming Gender: Social Change and Transgender Citizenship’, Sociological Research Online, 12(1):181-194 https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1469

C. T. Sullivan (2018) ‘Majesty in the city: experiences of an Aboriginal transgender sex worker in Sydney, Australia’, Gender, Place & Culture, 25(12): 1681-1702 https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1553853

M. J. Andrucki & D. J. Kaplan (2018) ‘Trans objects: materializing queer time in US transmasculine homes’, Gender, Place & Culture, 25(6): 781-798 https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1457014

O. Jenzen (2017) ‘Trans youth and social media: moving between counterpublics and the wider web’, Gender, Place & Culture, 24(11): 1626-1641 https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1396204

O. L. Haimson, A. Dame-Griff, E. Capello & Z. Richter (2019) ‘Tumblr was a trans technology: the meaning, importance, history, and future of trans technologies’, Feminist Media Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2019.1678505

T. Raun (2016) Out Online: Trans Self-Representation and Community Building on YouTube. London: Routledge https://www.routledge.com/Out-Online-Trans-Self-Representation-and-Community-Building-on-YouTube/Raun/p/book/9780367596620

Son Vivienne (2017) ‘“I Will Not Hate Myself because You Cannot Accept Me”: Problematizing Empowerment and Gender-Diverse Selfies’, Popular Communication, 15(2): 126–140 https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2016.1269906

M.Y. Chen (2010) ‘Everywhere Archives: Transgendering, Trans Asians, and the Internet’, Australian Feminist Studies, 25(64): 199-208 https://doi.org/10.1080/08164641003762503

J.N. Chen (2019) Trans Exploits: Trans of Color Cultures and Technologies in Movement. Durham: Duke University Press https://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/2636/Trans-ExploitsTrans-of-Color-Cultures-and

R. A. Pearce (2020) ‘A Methodology for the Marginalised: Surviving Oppression and Traumatic Fieldwork in the Neoliberal Academy’, Sociology, 54(4): 806-824 https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038520904918

Engagement with the “wrong body” model/trans medicalisation (rebuttal to the claim that trans theory necessarily reinforces a strict or medical model of gender)

T. M. Bettcher (2014) ‘Trapped in the wrong theory: Rethinking trans oppression and resistance’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 39(2): 383–406 https://doi.org/10.1086/673088

N. Sullivan (2008) ‘The Role of Medicine in the (Trans)Formation of “Wrong” Bodies’, Body & Society, 14(1): 105-116 https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X07087533

J.R. Latham (2019) ‘Axiomatic: Constituting “transsexuality” and trans sexualities in medicine’, Sexualities, 22 (1-2), 13-30 https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460717740258

J.R. Latham (2017) ‘Making and Treating Trans Problems: The Ontological Politics of Clinical Practices’, Studies in Gender and Sexuality, 18(1): 40-6 https://doi.org/10.1080/15240657.2016.1238682

S. Vogler (2019) ‘Determining Transgender: Adjudicating Gender Identity in U.S. Asylum Law’, Gender & Society, 33(3): 439-462 https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243219834043

A.P. Hilário (2020) ‘Rethinking trans identities within the medical and psychological community: a path towards the depathologization and self-definition of gender identification in Portugal?’, Journal of Gender Studies, 29(3): 245-256, https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2018.1544066

Non-binary and genderqueer subjectivities specifically (rebuttal to the erasure of non-binary identities – there is a growing field of empirical and theoretical work that looks at the complexities of non-binary and genderqueer identities and experiences)

H. Darwin (2020) ‘Challenging the Cisgender/Transgender Binary: Nonbinary People and the Transgender Label’, Gender & Society, 34(3):357-380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243220912256

H. Barbee & D. Schrock (2019) ‘Un/gendering Social Selves: How Nonbinary People Navigate and Experience a Binarily Gendered World’, Sociological Forum, 34(3): 572-593 https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12517

S. Monro (2019) ‘Non-binary and genderqueer: An overview of the field’, International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2-3): 126-131 https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1538841

C. Richards, W. P. Bouman, L. Seal, M-J. Barker, T.O. Nieder, G. T’Sjoen (2016) ‘Non-binary or genderqueer genders’, International Review of Psychology, 28(1): 95-102 https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1106446

S.Bower-Brown, S. Zadeh & V.Jadva (2021) ‘Binary-trans, non-binary and gender-questioning adolescents’ experiences in UK schools’, Journal of LGBT Youth, 1-19 https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2021.1873215

D. Cosgrove (2021) ‘“I am allowed to be myself”: A photovoice exploration of non-binary identity development and meaning-making’, Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 33(1): 78-102 https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2020.1850385

A. Vijlbrief, S. Saharso & H. Ghorashi (2020) ‘Transcending the gender binary: Gender non-binary young adults in Amsterdam’, Journal of LGBT Youth, 17(1): 89-106 https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2019.1660295

L. Nicholas (2019) ‘Queer ethics and fostering positive mindsets toward non-binary gender, genderqueer, and gender ambiguity’, International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2-3): 169-180 https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1505576

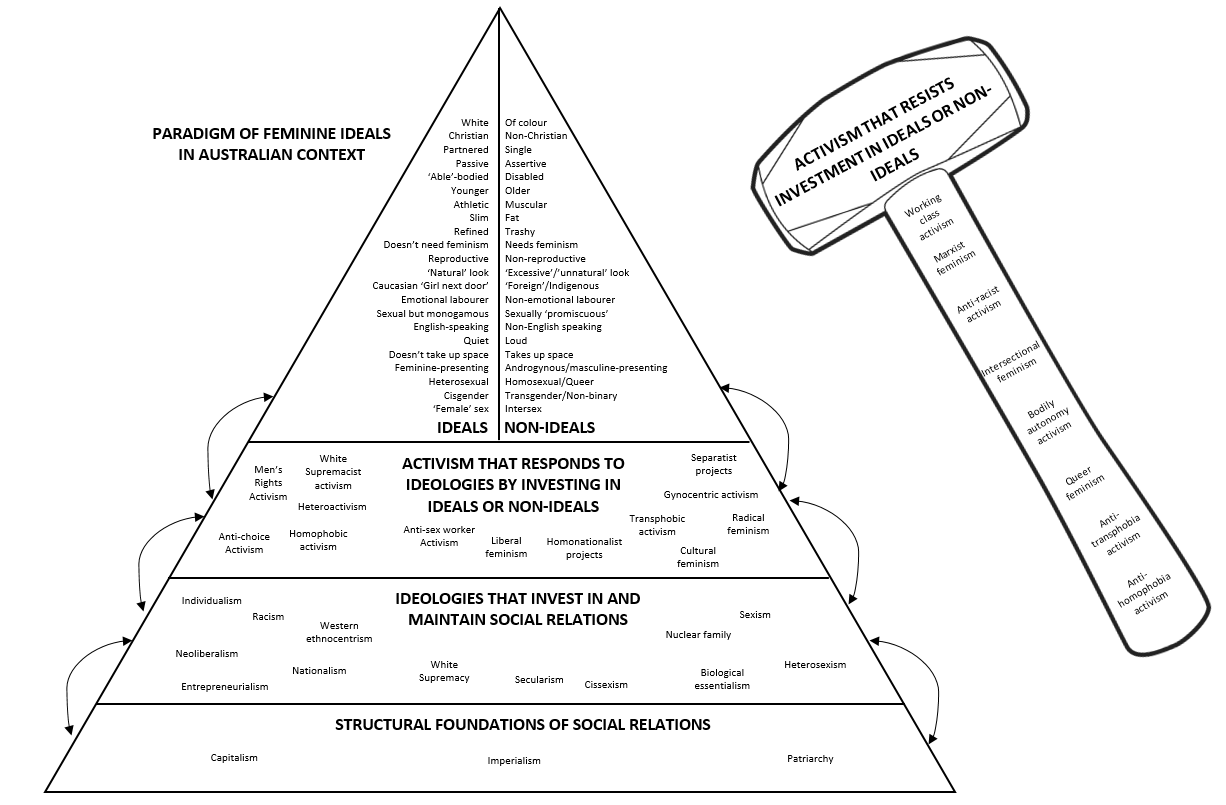

I like to think in visual terms, and the diagram above (click on it to enlarge) is an attempt to sum up how we might connect structure, activism, and norms in a useful way. I’ve included a hammer here as a kind of nuanced update to that “If I had a hammer” image.

I like to think in visual terms, and the diagram above (click on it to enlarge) is an attempt to sum up how we might connect structure, activism, and norms in a useful way. I’ve included a hammer here as a kind of nuanced update to that “If I had a hammer” image. At the very base are the “structural foundations”, which accounts for the economic, colonial, and gendered power structures that are the foundation of the dominant organisation of social relations in this context. Flowing from this foundation, but also feeding back into it, are the dominant ideologies that invest in and maintain these social relations. For example, neoliberalism is an ideology that supports capitalism. Similarly White supremacy is an ideology that supports imperialism. Flowing from this, there are various forms of activism that respond to these ideologies in ways that either bolster these ideologies or reject them. The activism that bolsters these ideologies also works toward cementing what is understood as the “ideals”.

At the very base are the “structural foundations”, which accounts for the economic, colonial, and gendered power structures that are the foundation of the dominant organisation of social relations in this context. Flowing from this foundation, but also feeding back into it, are the dominant ideologies that invest in and maintain these social relations. For example, neoliberalism is an ideology that supports capitalism. Similarly White supremacy is an ideology that supports imperialism. Flowing from this, there are various forms of activism that respond to these ideologies in ways that either bolster these ideologies or reject them. The activism that bolsters these ideologies also works toward cementing what is understood as the “ideals”. It is clear for example, that

It is clear for example, that  Perhaps this is what might mark out a new wave of (feminist and other) activism around femininity: challenging gender ideals without investing in non-ideals as the political response. From such a perspective, there is no femininity that is “empowered”. Power is exerted and ideals are enforced, but the reaction to this is to focus on the structural foundations and their ideological props rather than the individual effects alone (which might for some involve complicated attachments).

Perhaps this is what might mark out a new wave of (feminist and other) activism around femininity: challenging gender ideals without investing in non-ideals as the political response. From such a perspective, there is no femininity that is “empowered”. Power is exerted and ideals are enforced, but the reaction to this is to focus on the structural foundations and their ideological props rather than the individual effects alone (which might for some involve complicated attachments). As

As  So the story goes: “it gets better”. This is a common refrain of LGBTIQ youth services in Australia. “It gets better” refers to the promise that when you leave school, you won’t have to deal with bullies any longer – you’ll be free to live your life as a happy LGBTIQ person. Now, for many of us, this isn’t totally wrong. Leaving the social intensity of the schoolyard and becoming independent from family units, can mean that we are able to find new communities of acceptance.

So the story goes: “it gets better”. This is a common refrain of LGBTIQ youth services in Australia. “It gets better” refers to the promise that when you leave school, you won’t have to deal with bullies any longer – you’ll be free to live your life as a happy LGBTIQ person. Now, for many of us, this isn’t totally wrong. Leaving the social intensity of the schoolyard and becoming independent from family units, can mean that we are able to find new communities of acceptance. But how cruel might this hopeful promise be, when bigotry can be canvassed as state-sanctioned “legitimate debate”, as we are seeing now? When homophobic and transphobic ideas are not originating from the schoolyard itself – as we know,

But how cruel might this hopeful promise be, when bigotry can be canvassed as state-sanctioned “legitimate debate”, as we are seeing now? When homophobic and transphobic ideas are not originating from the schoolyard itself – as we know,  As

As  But cruel is the optimism of the segments of the “yes” campaign that refuse to confront the homophobia and transphobia emerging in the debate, and instead seek to win hearts and minds on the basis of respectability, normality, and the idea that “love” is indeed “love”. As Berlant argues, it is a cruel optimism that operates where we live with the toxic conditions of the present labouring under the view that the future will “somehow” deliver something better.

But cruel is the optimism of the segments of the “yes” campaign that refuse to confront the homophobia and transphobia emerging in the debate, and instead seek to win hearts and minds on the basis of respectability, normality, and the idea that “love” is indeed “love”. As Berlant argues, it is a cruel optimism that operates where we live with the toxic conditions of the present labouring under the view that the future will “somehow” deliver something better. And indeed it is cruelly optimistic to imagine what that future will entail if we do not question the social constitution of futurity in the first instance. As

And indeed it is cruelly optimistic to imagine what that future will entail if we do not question the social constitution of futurity in the first instance. As  This is precisely what we have seen playing out for over a decade, albeit more sharply in recent times, in the marriage equality debate. While the right have repeated the refrain, “think of the children”, the left too have taken up this mantle, constantly leaning on statistics about the welfare of queer youth or children from queer families in order to make a point of the utter sameness of the child under queer circumstances. In this envisioning, the queer child doesn’t queer the future, rather, the queerness of the child is contained in order to suggest that there is very little threat – only a slight extension – to the more conservative vision.

This is precisely what we have seen playing out for over a decade, albeit more sharply in recent times, in the marriage equality debate. While the right have repeated the refrain, “think of the children”, the left too have taken up this mantle, constantly leaning on statistics about the welfare of queer youth or children from queer families in order to make a point of the utter sameness of the child under queer circumstances. In this envisioning, the queer child doesn’t queer the future, rather, the queerness of the child is contained in order to suggest that there is very little threat – only a slight extension – to the more conservative vision. As the recent

As the recent  We might wonder about the astringency of Edelman’s anti-social thesis, in light of the fact that attachment to “same-sex marriage” is currently being enacted by many as a mode of survival. Many have thrown themselves into fighting for a yes campaign precisely in order to assist a striving toward a “getting better”. We might also question the limits of Edelman’s radical presentism and anti-futurity, and if a different kind of future envisioning might be possible without a cruel investment in inevitable progress.

We might wonder about the astringency of Edelman’s anti-social thesis, in light of the fact that attachment to “same-sex marriage” is currently being enacted by many as a mode of survival. Many have thrown themselves into fighting for a yes campaign precisely in order to assist a striving toward a “getting better”. We might also question the limits of Edelman’s radical presentism and anti-futurity, and if a different kind of future envisioning might be possible without a cruel investment in inevitable progress. As

As  Similarly

Similarly  But in making the negativity at the heart of things public rather than private, we can also become targeted as the problem rather than merely pointing out the problem. As

But in making the negativity at the heart of things public rather than private, we can also become targeted as the problem rather than merely pointing out the problem. As  While we focus solely on concepts like fairness and kindness, positivity, good stories, the “good homosexual”, or the “unqueer queer child”, the bad feelings at the heart of the marriage equality debate remain occluded and politically impotent. To fail to recognise and name the homophobia and transphobia that are proliferating under conservative discussions in the marriage equality debate is to inadvertently reiterate a narrative of a heteronormative future where “it gets better”. To engage in a queer hopefulness then, is not to shy away from negativity, but rather, to embrace the possible world that it reveals to us.

While we focus solely on concepts like fairness and kindness, positivity, good stories, the “good homosexual”, or the “unqueer queer child”, the bad feelings at the heart of the marriage equality debate remain occluded and politically impotent. To fail to recognise and name the homophobia and transphobia that are proliferating under conservative discussions in the marriage equality debate is to inadvertently reiterate a narrative of a heteronormative future where “it gets better”. To engage in a queer hopefulness then, is not to shy away from negativity, but rather, to embrace the possible world that it reveals to us. It is only in confronting those elements of the present that we would rather deny, from which a truly utopian vision might emerge. In this case, my educated hope is that we will have a marriage equality debate that confronts homophobia and transphobia, that embraces gender and sexual diversity, and that makes space for the LGBTIQ community well beyond the question of marriage.

It is only in confronting those elements of the present that we would rather deny, from which a truly utopian vision might emerge. In this case, my educated hope is that we will have a marriage equality debate that confronts homophobia and transphobia, that embraces gender and sexual diversity, and that makes space for the LGBTIQ community well beyond the question of marriage.