“What is the sound of a machine breaking down? What noise does this machine make as it refuses to stop? Today, when I woke, I was already exhausted” (Snack Syndicate, “Groundwork — Protocols For Listening in (and after) Social Isolation“)

I’ve been thinking a lot about consumption during lockdown. What we consume. Why we consume. Who usually makes our consumables. One of the things on repeat in the media at the moment is that because the economy is tanking we need to spend, consume, more. Even though people are losing their jobs left and right, we are being encouraged not to save. In Australia even our retirement funds have been opened up for us to spend. Graphs on the nightly news track consumer confidence. We’re spending more in supermarkets and on homewares but less on retail and restaurants. Across the board those still with jobs are saving too much, and those without have nothing spare to spend. The rich lament that there’s “just nothing to spend money on“. In the UK young people have been told to go out and spend for the country, but are now being blamed for the spike in COVID-19 cases. Being a “good consumer” at the moment is fraught, to say the least.

This week The Guardian started a discussion about “lockdown shopping“, for readers to contribute stories of purchases in isolation. Many of the comments noted a sense of “doing one’s bit” to help the economy, by buying things. But well before COVID-19 much of our sense of agency had been whittled down to our consumer power. I’ve noticed the impulse comes out when things go wrong. When a friend is going through a tough time my first instinct is often “what can I buy them?” (flowers, plants, chocolate, etc) instead of “how can I be there for them?”. Of course a gift signals care and concern but it is interesting to think how this impulse might also reveal how I defer first to consumption, rather than say, creation or care.

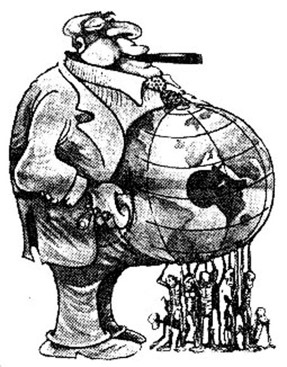

Trying to prop the economy up with spending keeps us in an impossible bind. Many of us are not spending enough but we’re also not saving enough for our future livelihoods. Right now being encouraged to spend money to keep the broken wheels of capitalism spinning feels a bit like being asked to contribute to a giant Go Fund Me so that everyone can still have a job.

Under capitalism the donations are never going to go into the right pockets. Even in countries like Australia where governments have provided funding supports (though these are quickly being slashed) the ruling class have been skimming them for profit. In real terms wages have gone down over the COVID-19 period while profits have gone up, with shareholders scooping up subsidy gains. Capital stays winning while labour loses. It’s enough to make your blood boil. If you’re like me I’d wager it may also be enough to make you reach for the dopamine hit provided by online shopping. It’s understandable to pursue small pleasures in the big disaster of it all.

One of my own recent rage/despair purchases was the September edition of British Vogue. I’ve been buying British Vogue on and off since Edward Enninful took the reins, who promised to take the fashion magazine in more radical directions (the fact that Teen Vogue has gone rogue since going online is also fascinating, but another story). The September 2020 front cover features Marcus Rashford and Adwoa Aboah in Black-Pantheresque attire, with the banner “ACTIVISM NOW: THE FACES OF HOPE”. The four-page fold out features over a dozen activists and commentators, largely connected to the Black Lives Matter movement. But flip the cover pages over and there’s an enormous spread from fashion house Ralph Lauren, featuring a diverse cast of mostly Black and Brown models all decked out in POLO. The ad states “We believe in a quality of life that is authentic and optimistic – one that embraces a spirit of togetherness, and honors the individual beauty in each of us”. What this juxtaposition of the brand with the cover amounts to is that the radical focus on activists is immediately recuperated. Activism is sold back to us the moment it is featured.

The overall theme of the issue is “hope”, and many of the advertisements proclaim radically generic ideas like “Hope is not a trend” or “We are one”. Much of the content is also dedicated to leading figures in the fashion industry talking about what needs to change in light of COVID-19 – namely that the furious churn of fashion needs to slow down. But as dynastic designers like Donatella Versace state their new drive to make “everything sustainable”, the contradiction is palpable given their exceptional wealth and intimate ties to the very richest of the ruling class. There can be no sustainability, no justice, no peace, within a system fundamentally geared toward profit, of which the fashion industry plays no small part. This is precisely an industry where creativity has been distorted into hyper-consumption, and where the artistry of couture is reserved for those at the top. Just like every other industry, there is no real way to be ethical under this deeply extractive system.

I am not making these judgements of the fashion industry from afar. I love fashion, and I love fashion magazines. I too recently bought some pleated pants, under the auspice of “doing my bit” for the economy (and trying to achieve the “dark academia” trend). It made me feel good to purchase something and receive a parcel in the mail. But COVID-19 has exposed an unbridgeable rift in capitalism that was always in its fabric. No amount of pant buying is going to keep me or my friends employed. And there is no way to make for-profit driven business “sustainable”. We knew it already, but now it’s confirmed: this is a profoundly unsustainable system.

I recently attended an online reading group where we discussed the piece “Groundwork — Protocols For Listening in (and after) Social Isolation” by Sydney-based poetry team Snack Syndicate. The piece offers a meditation on labour practices under lockdown, and in it they ask “What is the sound of a machine breaking down?” I read this question to (maybe) mean, what might the death throes of the oppressive structure actually sound like, if we listen? In the reading group I had no answers, only vague gestures toward the utopian possibilities of imagining different worlds. But reading British Vogue this week I felt like I could, maybe, hear the machine slightly breaking.

Not everything can be easily recuperated. Despite the best efforts of advertisers, an ad declaring “hope for the future” is always going to jar with actual demands of activists who want an end to white supremacy, real action on climate catastrophe, and a new order – not the old normal. The sound of the machine breaking is the contradictions getting so wide and deep that you can hear the cracks. Even if brands do try and sell mass uprisings back to us sometimes, these always stay incredibly surface-level. They have to, because actually smashing up the current (racist, sexist, homophobic) system and eating the rich isn’t really something a CEO is going to want to promote.

You can’t buy change. The less that we can think of our power in terms of consumption the better. So many actions championed pre-COVID – use less plastic, go vegan, install solar panels – have been well-intentioned but have primed us to think of our political power in terms of consumption.

Going vegan and going off-grid is actually easy for many of the readers of British Vogue to achieve. The very wealthy can employ someone else to do their shopping for them, set up their houses, install the right things. British Vogue shows that the 1% are doing great at adapting to (and selling) “clean beauty” and “ethical fashion”. Consumption as power washes the hands of those that can afford to consume “right”, and does nothing to address the underlying system of exploitation (that they are running!) that means we have mass produced plastic, factory farming, and fossil fuel dependance, etc, in the first place.

All of this is to say that I don’t think you should feel bad about your current consumption or lack thereof. No amount of purchasing power is going to save us right now. Sure, keep buying local, buy the plants and the pants. Or don’t. Either way make sure you listen out for the cracks, and dive right in.

Many of us are reading so much about COVID-19 at the moment, that it seems nothing else exists, or can exist. With everything cancelled and our social worlds rapidly shrinking, there is, quite literally, not much else to report on. In Australia we’re just at the crest of the wave, a few weeks (if that) behind some European nations in terms of cases. But our public health messaging has been wildly mixed, and as a result ordinary people and businesses are all over the shop when it comes to changing their daily lives and routines in response. While one friend is worried she won’t see her parents for months because of state border lockdowns, another is hosting a dinner party. While public libraries were some of the first spaces to shut down (even though they are the only place some people can access the Internet), the boutique pet store on my street remains open. Some cafes have been serving only through windows while others (until the shut down – though this is still unclear) seemed wildly unaffected. We could analyse this as a total failure of public health messaging, but how to analyse the feelings associated with this unevenness as we navigate our lives right now?

Many of us are reading so much about COVID-19 at the moment, that it seems nothing else exists, or can exist. With everything cancelled and our social worlds rapidly shrinking, there is, quite literally, not much else to report on. In Australia we’re just at the crest of the wave, a few weeks (if that) behind some European nations in terms of cases. But our public health messaging has been wildly mixed, and as a result ordinary people and businesses are all over the shop when it comes to changing their daily lives and routines in response. While one friend is worried she won’t see her parents for months because of state border lockdowns, another is hosting a dinner party. While public libraries were some of the first spaces to shut down (even though they are the only place some people can access the Internet), the boutique pet store on my street remains open. Some cafes have been serving only through windows while others (until the shut down – though this is still unclear) seemed wildly unaffected. We could analyse this as a total failure of public health messaging, but how to analyse the feelings associated with this unevenness as we navigate our lives right now? What this lopsided shut down of daily life adds up to is that we, as a populace, inhabit different affective landscapes. That is: we’re feeling different things, living in different worlds, even as the same crisis is affecting absolutely all of us. For those who have had to radically alter their working life (working from home, perhaps with added caring responsibilities) or have lost their jobs this past fortnight, the reality of things is probably much closer, though tempered by the immediate demands of life logistics, care, and survival. For those who have had to stay working as per usual things might feel strangely normal, or, simply that we are living in the shadow of something serious to come but not yet here. Some of us check live news feeds all day, while others don’t have the space or inclination (and in any case, the news and guidelines change by the hour, minute). The point is that we’re all arriving at conclusions at different times. Some people are already totally socially distanced and staying at home, while others continue to maintain many face-to-face networks. We are living in different (emotional) worlds, and the effect of that is, frankly, jarring.

What this lopsided shut down of daily life adds up to is that we, as a populace, inhabit different affective landscapes. That is: we’re feeling different things, living in different worlds, even as the same crisis is affecting absolutely all of us. For those who have had to radically alter their working life (working from home, perhaps with added caring responsibilities) or have lost their jobs this past fortnight, the reality of things is probably much closer, though tempered by the immediate demands of life logistics, care, and survival. For those who have had to stay working as per usual things might feel strangely normal, or, simply that we are living in the shadow of something serious to come but not yet here. Some of us check live news feeds all day, while others don’t have the space or inclination (and in any case, the news and guidelines change by the hour, minute). The point is that we’re all arriving at conclusions at different times. Some people are already totally socially distanced and staying at home, while others continue to maintain many face-to-face networks. We are living in different (emotional) worlds, and the effect of that is, frankly, jarring. This is not to mention that at this juncture, with ordinary routines gone and a fluctuating and uncertain future, our sense of time is out of kilter. Something that happened yesterday might feel like weeks ago, while imagining tomorrow can seem like a big question mark. All normal sense of time lost. Even if we’re at home, trying to settle into the new “local”, it’s a pretty lumpy and warped everyday to traverse.

This is not to mention that at this juncture, with ordinary routines gone and a fluctuating and uncertain future, our sense of time is out of kilter. Something that happened yesterday might feel like weeks ago, while imagining tomorrow can seem like a big question mark. All normal sense of time lost. Even if we’re at home, trying to settle into the new “local”, it’s a pretty lumpy and warped everyday to traverse. When I came back to Melbourne, people were just going about their daily lives as normal. Talking to friends I tried to make them feel my panic, my newly-found prepper attitude (make sure you have a full tank of petrol!), because I was living in one affective place and they another. I wanted to be in the same place, so we could weather the storm together. But I learnt that even if you really want people to be on the same page as you – full of either the same amount of despair or hope that you hold – you will probably be disappointed. People deal with things in their own way and time.

When I came back to Melbourne, people were just going about their daily lives as normal. Talking to friends I tried to make them feel my panic, my newly-found prepper attitude (make sure you have a full tank of petrol!), because I was living in one affective place and they another. I wanted to be in the same place, so we could weather the storm together. But I learnt that even if you really want people to be on the same page as you – full of either the same amount of despair or hope that you hold – you will probably be disappointed. People deal with things in their own way and time. But it also makes me wonder, what am I clinging to? What parts of the (already broken) system am I trying to grasp onto, as everything changes? People maintain feelings of normalcy as an act of survival.

But it also makes me wonder, what am I clinging to? What parts of the (already broken) system am I trying to grasp onto, as everything changes? People maintain feelings of normalcy as an act of survival.

Bisexuals (and especially bisexual men) have often been seen to “contaminate” straight life. This was most explicitly seen in the midst of the AIDS crisis, during which bisexuals were represented as adulterous hyper-sexual types who risked spreading the disease to the “normal” population. Similarly, gay communities have rejected bisexuals as “risky”, as seen in the 1990s following a rise in homophobic street attacks when the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras effectively

Bisexuals (and especially bisexual men) have often been seen to “contaminate” straight life. This was most explicitly seen in the midst of the AIDS crisis, during which bisexuals were represented as adulterous hyper-sexual types who risked spreading the disease to the “normal” population. Similarly, gay communities have rejected bisexuals as “risky”, as seen in the 1990s following a rise in homophobic street attacks when the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras effectively

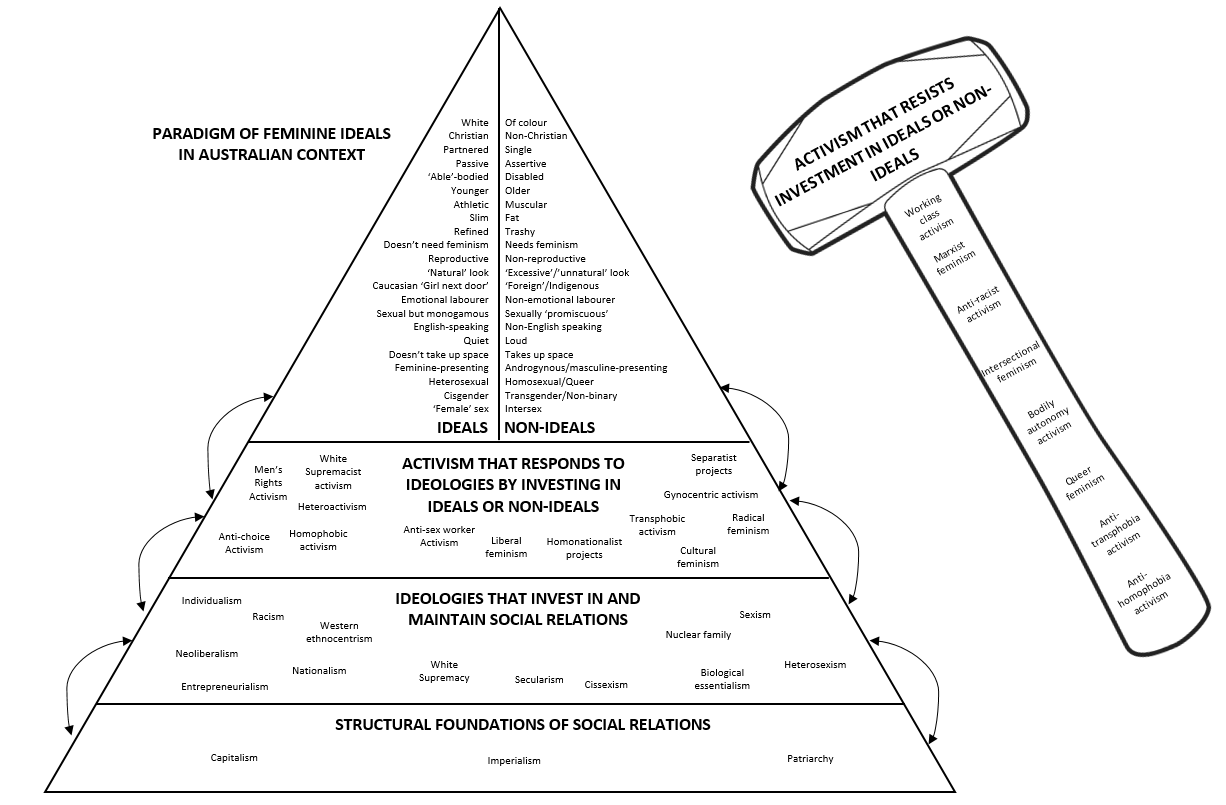

I like to think in visual terms, and the diagram above (click on it to enlarge) is an attempt to sum up how we might connect structure, activism, and norms in a useful way. I’ve included a hammer here as a kind of nuanced update to that “If I had a hammer” image.

I like to think in visual terms, and the diagram above (click on it to enlarge) is an attempt to sum up how we might connect structure, activism, and norms in a useful way. I’ve included a hammer here as a kind of nuanced update to that “If I had a hammer” image. At the very base are the “structural foundations”, which accounts for the economic, colonial, and gendered power structures that are the foundation of the dominant organisation of social relations in this context. Flowing from this foundation, but also feeding back into it, are the dominant ideologies that invest in and maintain these social relations. For example, neoliberalism is an ideology that supports capitalism. Similarly White supremacy is an ideology that supports imperialism. Flowing from this, there are various forms of activism that respond to these ideologies in ways that either bolster these ideologies or reject them. The activism that bolsters these ideologies also works toward cementing what is understood as the “ideals”.

At the very base are the “structural foundations”, which accounts for the economic, colonial, and gendered power structures that are the foundation of the dominant organisation of social relations in this context. Flowing from this foundation, but also feeding back into it, are the dominant ideologies that invest in and maintain these social relations. For example, neoliberalism is an ideology that supports capitalism. Similarly White supremacy is an ideology that supports imperialism. Flowing from this, there are various forms of activism that respond to these ideologies in ways that either bolster these ideologies or reject them. The activism that bolsters these ideologies also works toward cementing what is understood as the “ideals”. It is clear for example, that

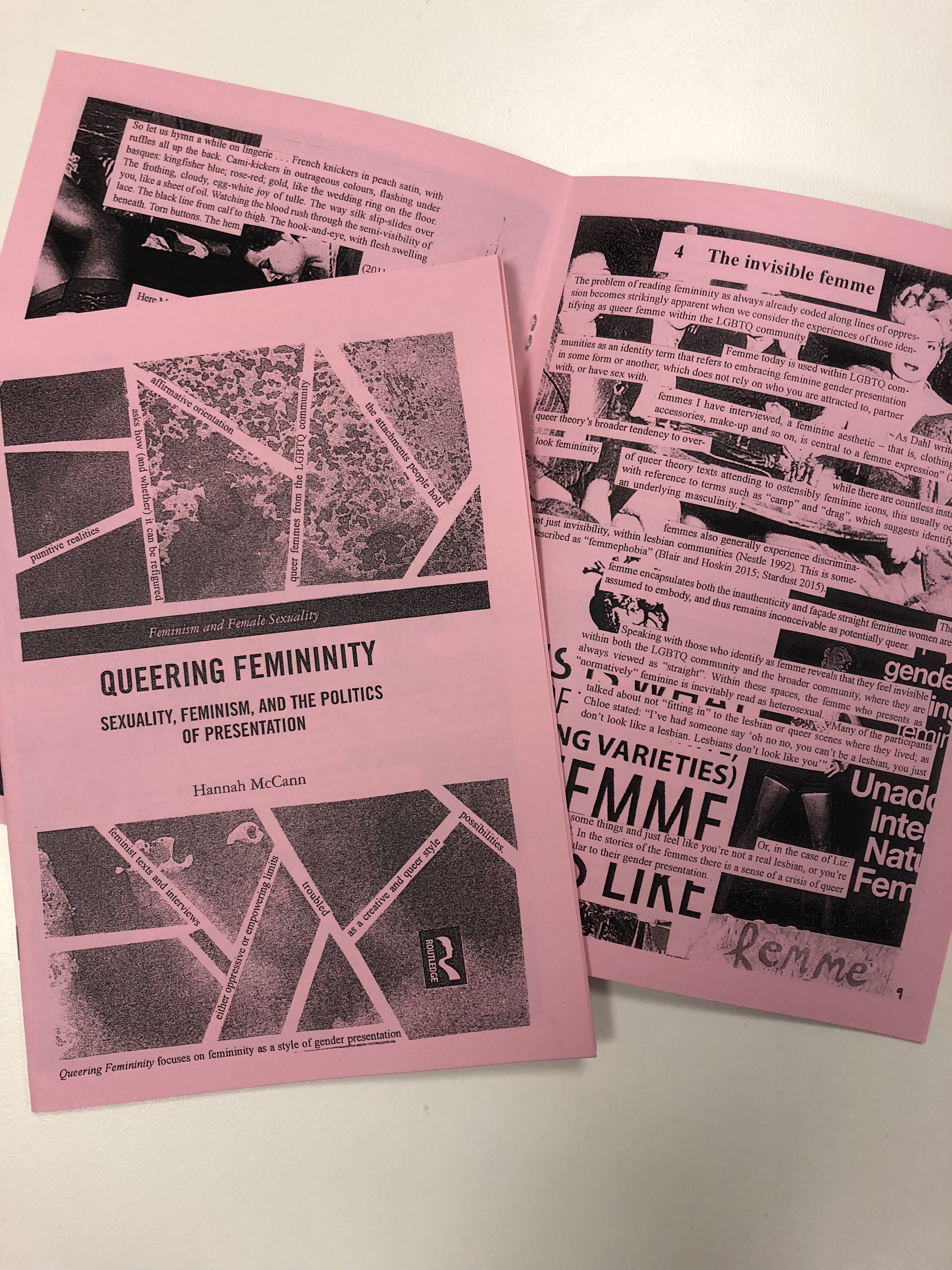

It is clear for example, that  Perhaps this is what might mark out a new wave of (feminist and other) activism around femininity: challenging gender ideals without investing in non-ideals as the political response. From such a perspective, there is no femininity that is “empowered”. Power is exerted and ideals are enforced, but the reaction to this is to focus on the structural foundations and their ideological props rather than the individual effects alone (which might for some involve complicated attachments).

Perhaps this is what might mark out a new wave of (feminist and other) activism around femininity: challenging gender ideals without investing in non-ideals as the political response. From such a perspective, there is no femininity that is “empowered”. Power is exerted and ideals are enforced, but the reaction to this is to focus on the structural foundations and their ideological props rather than the individual effects alone (which might for some involve complicated attachments). Yet, Lee Alexander McQueen’s vision of the possibilities of fashion to affect us on a profound emotional level juxtaposes such critiques. Tracking the autobiographical aspects of McQueen’s design, this documentary offers us a sense of artistry that cuts through ordinary understandings of fashion in terms of trends, mass production, and surface.

Yet, Lee Alexander McQueen’s vision of the possibilities of fashion to affect us on a profound emotional level juxtaposes such critiques. Tracking the autobiographical aspects of McQueen’s design, this documentary offers us a sense of artistry that cuts through ordinary understandings of fashion in terms of trends, mass production, and surface. McQueen described his shows as “what’s buried in people’s psyches”. One of the things that I love most about this documentary is the use of home footage from McQueen himself, which offers us an intensely intimate glimpse of the designer. We not only get a sense of McQueen’s mind – and his obsession with death, life, and beauty – most importantly I think, we get to see the tyranny of maintaining creativity despite the stifling economics of fashion.

McQueen described his shows as “what’s buried in people’s psyches”. One of the things that I love most about this documentary is the use of home footage from McQueen himself, which offers us an intensely intimate glimpse of the designer. We not only get a sense of McQueen’s mind – and his obsession with death, life, and beauty – most importantly I think, we get to see the tyranny of maintaining creativity despite the stifling economics of fashion. McQueen once said, “My sister is an amazing artist. My brother is an amazing artist. Amazing. Much better than I am. The difference is, they thought they had no chance but to do a manual job. That really upsets me”. To survive as a designer early in his career, McQueen had to live on almost nothing, and hide his fashion work from the dole office so that he could continue receiving benefits.

McQueen once said, “My sister is an amazing artist. My brother is an amazing artist. Amazing. Much better than I am. The difference is, they thought they had no chance but to do a manual job. That really upsets me”. To survive as a designer early in his career, McQueen had to live on almost nothing, and hide his fashion work from the dole office so that he could continue receiving benefits. To quote Elizabeth Wilson again, “Out of the cracks in the pavements of cities grow the weeds that begin to rot the fabric”. In other words, while we might hold reasonable ambivalence about the nature of fashion in terms of the expectations and norms that it reproduces, fashion can also provide an experimental and resistant space for a creative reimagining of identity that “rot[s] the fabric” of these same rules.

To quote Elizabeth Wilson again, “Out of the cracks in the pavements of cities grow the weeds that begin to rot the fabric”. In other words, while we might hold reasonable ambivalence about the nature of fashion in terms of the expectations and norms that it reproduces, fashion can also provide an experimental and resistant space for a creative reimagining of identity that “rot[s] the fabric” of these same rules. For

For  In her article, Freeman praises recent protests against the

In her article, Freeman praises recent protests against the  I was shocked that The Guardian would run this on

I was shocked that The Guardian would run this on  Luckily, changes to the GRA would reduce the clinical barriers needed to have gender identity recognised, which would mean less stress and burden for trans people and would reduce some of the pathologising elements of the process. If gender was truly liberated, we wouldn’t need to diagnose what expressions of gender are “normal”, we would celebrate a diversity of expressions, embodiments and feelings.

Luckily, changes to the GRA would reduce the clinical barriers needed to have gender identity recognised, which would mean less stress and burden for trans people and would reduce some of the pathologising elements of the process. If gender was truly liberated, we wouldn’t need to diagnose what expressions of gender are “normal”, we would celebrate a diversity of expressions, embodiments and feelings. As

As  Freeman claims that there is a massive issue with trans feminists who critique the centring of reproductive systems. She states, “I’m trying to think of anything more patriarchal than telling women to stop fussing about vaginas at a Women’s March”. What Freeman misses is that the issue isn’t talking about bodies and the material experience of gender altogether, the problem is creating a reductive version of feminism where vagina = woman and where this is made into the central focus of collective action. This doesn’t mean we can’t talk about issues like abortion, pregnancy, or periods either (all issues which affect a range of gendered peoples), it just means that we shouldn’t make biology the basis for our collective resistance.

Freeman claims that there is a massive issue with trans feminists who critique the centring of reproductive systems. She states, “I’m trying to think of anything more patriarchal than telling women to stop fussing about vaginas at a Women’s March”. What Freeman misses is that the issue isn’t talking about bodies and the material experience of gender altogether, the problem is creating a reductive version of feminism where vagina = woman and where this is made into the central focus of collective action. This doesn’t mean we can’t talk about issues like abortion, pregnancy, or periods either (all issues which affect a range of gendered peoples), it just means that we shouldn’t make biology the basis for our collective resistance. The claim that somehow “predatory men” will be emboldened to “come into female-only spaces unchallenged” is a transphobic furphy that’s been trotted out by right wing commentators for a long time now, and that has been

The claim that somehow “predatory men” will be emboldened to “come into female-only spaces unchallenged” is a transphobic furphy that’s been trotted out by right wing commentators for a long time now, and that has been  If all of this seems pretty basic, it’s because it is. Fundamentally it doesn’t matter what the relationship between biology (“sex”) and identity (“gender”) is, what really matters is treating human beings with dignity and celebrating the possibilities of gender. Because loosening the rules of gender, understanding gender and sexism beyond biology, talking about body issues but not reducing people to bodies, and thinking about how to have solidarity around the lived experiences of gender, should be fundamental to feminism. The alternative – the world that Freeman seeks to enforce – is not only a trans-exclusionary, it works against what decades of feminists have been fighting for.

If all of this seems pretty basic, it’s because it is. Fundamentally it doesn’t matter what the relationship between biology (“sex”) and identity (“gender”) is, what really matters is treating human beings with dignity and celebrating the possibilities of gender. Because loosening the rules of gender, understanding gender and sexism beyond biology, talking about body issues but not reducing people to bodies, and thinking about how to have solidarity around the lived experiences of gender, should be fundamental to feminism. The alternative – the world that Freeman seeks to enforce – is not only a trans-exclusionary, it works against what decades of feminists have been fighting for. Like many in the Australian LGBTIQ community, I am exhausted by the marriage equality “debate” that we are being subjected to. The nature of this atomised survey is that we’re supposed to stay positive and upbeat, to try and convince everyone that we’re “normal” and have no other agenda than “love”. But being glass-half-full optimistic in this situation takes a lot of mental and emotional energy. That’s why it was so deeply infuriating to see our Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull—the person whose cowardice means we even have to endure this survey—on TV suggesting that the ‘yes’ campaign needs to lighten up about homophobia.

Like many in the Australian LGBTIQ community, I am exhausted by the marriage equality “debate” that we are being subjected to. The nature of this atomised survey is that we’re supposed to stay positive and upbeat, to try and convince everyone that we’re “normal” and have no other agenda than “love”. But being glass-half-full optimistic in this situation takes a lot of mental and emotional energy. That’s why it was so deeply infuriating to see our Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull—the person whose cowardice means we even have to endure this survey—on TV suggesting that the ‘yes’ campaign needs to lighten up about homophobia.

It’s important to take a step back here and recognise Turnbull’s comments for what they are:

It’s important to take a step back here and recognise Turnbull’s comments for what they are:  What all of this reveals is that whatever the outcome of the survey, Turnbull is firmly not on the side of the LGBTIQ community.

What all of this reveals is that whatever the outcome of the survey, Turnbull is firmly not on the side of the LGBTIQ community. As

As  So the story goes: “it gets better”. This is a common refrain of LGBTIQ youth services in Australia. “It gets better” refers to the promise that when you leave school, you won’t have to deal with bullies any longer – you’ll be free to live your life as a happy LGBTIQ person. Now, for many of us, this isn’t totally wrong. Leaving the social intensity of the schoolyard and becoming independent from family units, can mean that we are able to find new communities of acceptance.

So the story goes: “it gets better”. This is a common refrain of LGBTIQ youth services in Australia. “It gets better” refers to the promise that when you leave school, you won’t have to deal with bullies any longer – you’ll be free to live your life as a happy LGBTIQ person. Now, for many of us, this isn’t totally wrong. Leaving the social intensity of the schoolyard and becoming independent from family units, can mean that we are able to find new communities of acceptance. But how cruel might this hopeful promise be, when bigotry can be canvassed as state-sanctioned “legitimate debate”, as we are seeing now? When homophobic and transphobic ideas are not originating from the schoolyard itself – as we know,

But how cruel might this hopeful promise be, when bigotry can be canvassed as state-sanctioned “legitimate debate”, as we are seeing now? When homophobic and transphobic ideas are not originating from the schoolyard itself – as we know,  As

As  But cruel is the optimism of the segments of the “yes” campaign that refuse to confront the homophobia and transphobia emerging in the debate, and instead seek to win hearts and minds on the basis of respectability, normality, and the idea that “love” is indeed “love”. As Berlant argues, it is a cruel optimism that operates where we live with the toxic conditions of the present labouring under the view that the future will “somehow” deliver something better.

But cruel is the optimism of the segments of the “yes” campaign that refuse to confront the homophobia and transphobia emerging in the debate, and instead seek to win hearts and minds on the basis of respectability, normality, and the idea that “love” is indeed “love”. As Berlant argues, it is a cruel optimism that operates where we live with the toxic conditions of the present labouring under the view that the future will “somehow” deliver something better. And indeed it is cruelly optimistic to imagine what that future will entail if we do not question the social constitution of futurity in the first instance. As

And indeed it is cruelly optimistic to imagine what that future will entail if we do not question the social constitution of futurity in the first instance. As  This is precisely what we have seen playing out for over a decade, albeit more sharply in recent times, in the marriage equality debate. While the right have repeated the refrain, “think of the children”, the left too have taken up this mantle, constantly leaning on statistics about the welfare of queer youth or children from queer families in order to make a point of the utter sameness of the child under queer circumstances. In this envisioning, the queer child doesn’t queer the future, rather, the queerness of the child is contained in order to suggest that there is very little threat – only a slight extension – to the more conservative vision.

This is precisely what we have seen playing out for over a decade, albeit more sharply in recent times, in the marriage equality debate. While the right have repeated the refrain, “think of the children”, the left too have taken up this mantle, constantly leaning on statistics about the welfare of queer youth or children from queer families in order to make a point of the utter sameness of the child under queer circumstances. In this envisioning, the queer child doesn’t queer the future, rather, the queerness of the child is contained in order to suggest that there is very little threat – only a slight extension – to the more conservative vision. As the recent

As the recent  We might wonder about the astringency of Edelman’s anti-social thesis, in light of the fact that attachment to “same-sex marriage” is currently being enacted by many as a mode of survival. Many have thrown themselves into fighting for a yes campaign precisely in order to assist a striving toward a “getting better”. We might also question the limits of Edelman’s radical presentism and anti-futurity, and if a different kind of future envisioning might be possible without a cruel investment in inevitable progress.

We might wonder about the astringency of Edelman’s anti-social thesis, in light of the fact that attachment to “same-sex marriage” is currently being enacted by many as a mode of survival. Many have thrown themselves into fighting for a yes campaign precisely in order to assist a striving toward a “getting better”. We might also question the limits of Edelman’s radical presentism and anti-futurity, and if a different kind of future envisioning might be possible without a cruel investment in inevitable progress. As

As  Similarly

Similarly  But in making the negativity at the heart of things public rather than private, we can also become targeted as the problem rather than merely pointing out the problem. As

But in making the negativity at the heart of things public rather than private, we can also become targeted as the problem rather than merely pointing out the problem. As  While we focus solely on concepts like fairness and kindness, positivity, good stories, the “good homosexual”, or the “unqueer queer child”, the bad feelings at the heart of the marriage equality debate remain occluded and politically impotent. To fail to recognise and name the homophobia and transphobia that are proliferating under conservative discussions in the marriage equality debate is to inadvertently reiterate a narrative of a heteronormative future where “it gets better”. To engage in a queer hopefulness then, is not to shy away from negativity, but rather, to embrace the possible world that it reveals to us.

While we focus solely on concepts like fairness and kindness, positivity, good stories, the “good homosexual”, or the “unqueer queer child”, the bad feelings at the heart of the marriage equality debate remain occluded and politically impotent. To fail to recognise and name the homophobia and transphobia that are proliferating under conservative discussions in the marriage equality debate is to inadvertently reiterate a narrative of a heteronormative future where “it gets better”. To engage in a queer hopefulness then, is not to shy away from negativity, but rather, to embrace the possible world that it reveals to us. It is only in confronting those elements of the present that we would rather deny, from which a truly utopian vision might emerge. In this case, my educated hope is that we will have a marriage equality debate that confronts homophobia and transphobia, that embraces gender and sexual diversity, and that makes space for the LGBTIQ community well beyond the question of marriage.

It is only in confronting those elements of the present that we would rather deny, from which a truly utopian vision might emerge. In this case, my educated hope is that we will have a marriage equality debate that confronts homophobia and transphobia, that embraces gender and sexual diversity, and that makes space for the LGBTIQ community well beyond the question of marriage.