Dear Anna,

I have been thinking about how I might write a review of The Modern, given my love of it, but also given our prior entanglement. What are the ethics of critique when the personal is unavoidable? I am sure this is a legitimate genre of criticism and I am just being naive, but I am putting this in a letter to you (to everyone) to avoid any doubt about the conflict of interest.

When we first started dating I sent one of my friends a text: What do you do if your girlfriend turns out to be your favourite author? Wouldn’t that be wild? I will never know, we did not stay girlfriends.

You once said to me that you felt as if everything you wrote was for me, that you imagined me as the reader. I know that cannot – would not reasonably – be the case anymore, but it felt so special reading The Modern, knowing you, having known you, for some of the time that you were writing it. Against postmodernism, you as author were so alive to me in this.

I wanted to buy a copy in support, but I also narcissistically wondered if I was reflected in the text. I analysed your descriptions of Robert, Cara, Sally, Emily, and other subsidiary characters, for any hints. In fact, they all seemed more like versions of you. Maybe this is how writing always works. Everyone was much too erudite or cool or modern to feel anything like me, but on reflection I can see that some of the worst elements of my anxious-avoidant attachment style are, perhaps, in there.

I flinch, for instance, at Cara deleting all traces of Sophia on her social media: “It felt as if she was determined to erase memories of our pleasant moments, ashamed to admit that we’d spent time together, as if she was trying to create a narrative of her life in which I meant nothing”. I regret it. It made me think about how we efface surfaces when we cannot bare their depth. The desire to negate intimacy in order to stay a step ahead of rejection.

We don’t really get to know Cara in The Modern, she remains two-dimensional to the reader but hyper-real to Sophia. I think this is part of the point, an exploration of what it feels like to have an infatuation where the other person becomes a slate onto which you project. I read a review of the novel that described it as “solipsistic” but why aren’t women allowed to look in the mirror?

When you are falling in love, everything feels intertextual and full of portent. Songs playing in restaurants, whether flowers in a vase stay closed, the weather forecast – all take on special meaning. Yet I wrote in my diary I felt “haunted” by romance when we were together, that all of the beautiful things we encountered felt jarring with my internal unease. Perhaps it was, like Sophia, because I was in love with someone else. You and I talked openly about my other love, and I wondered whether your tolerance was simply because of interest in a writerly way. After The Modern, I think it is because you deeply understand the multiple directions love can pull you in simultaneously, and the odd formations that friendship can take. You have no judgement of it.

As you know, the last day with my other love involved rowing down the river to celebrate exactly one year of our friendship. As we ate our picnic floating on the water – and before I could declare my love – he played the song “Can’t We Be Friends” from his phone. I recounted all this to you later and you said it was too trite to be literary.

I cherish that this is a novel with Frank O’Hara and Grace Hartigan at the heart of it. Forgetting your love of them, I had serendipitously re-read Meditations on an Emergency only days before The Modern arrived in my mailbox. “In times of crisis, we must all decide again and again whom we love”. Most significantly, The Modern is radical in not shying away from love as the centre of analysis. It is not a romance novel, but it is all about romance. Crushes are often understood as frivolous, juvenile, and above all, feminine. The Modern rejects none of this, treating the “unserious” with extreme care and detail. I recall you giving me Lunch Poems when we were dating. You said you had a spare copy, it was no big deal, it really meant nothing. When I leaf through it now, I have questions. “Is this love, now that the first love/has finally died, where there were no impossibilities?” Frank and Grace’s love for one another is the model of the most beautiful “unrequited”, “unrealised” love.

I met a writer at a book event recently, and she asked if I read poetry, and when and why I started reading it. I told her earnestly that there were two influences: my year eight English teacher (Mr Mansfield) on whom I had an enormous crush, and you, who asked me on our first date who my favourite poet was, and I couldn’t really answer. After that date I was determined to commit to poetry, to know it. You and I don’t talk anymore, but I still read poetry.

The Modern‘s mode – the crush as literary – is what makes it so special. I know that it has/will be compared to other melancholic novels by women (ones which I also love), but it is standalone in its occupation of queerness. While others in this genre are haunted by bisexuality (The Bell Jar), or relegate conflicts about sexual identity to the background (Conversations With Friends), The Modern addresses the complexity head-on. You capture the tensions of bisexuality so perfectly. The mixed desires, the different social scripts, sex, bodies, the longing for queerness. This, for me, makes it a bisexual novel for the ages. As Sophia reflects, “I felt too nervous to go to the Pride March alone. I lay in bed looking at photographs of women in t-shirts that read BISEXUALS ARE NOT CONFUSED. I was confused, though…”.

Primarily, The Modern is so witty. I laughed aloud so many times at the pluck of it, forced my partner to hear excerpts. I loved all of the reverent references to artworks, even those I did not know and made me feel inculte. I loved the camp obsession with the bridal, reflections on the ambivalence of marriage. I didn’t believe Robert’s ability to quote Sophia’s favourite literary texts, but it is an interesting fantasy, I too can imagine loving such a Philosophy Boy. I loved all the references to the sweet and sugary, the way you describe fireworks, the throwaway comment about Sophia only eating pink foods when she was sad, as if that is normal sad behaviour. I am reminded of the summer that we ate fairybread for lunch, your serious and dedicated whimsy.

Years ago when you told me the title of your novel, I worried that it would be unsearchable, lost in more general results. Like that band that called themselves “!!!” that no one could pronounce nor look up, whose songs have been forgotten because their punctuation was too cool.

I hope people find and read The Modern. If they don’t, I hope you keep writing anyway. I can’t wait to keep reading you.

“It is most modern to affirm someone“.

Love, H

You can read more about The Modern here and order a copy here.

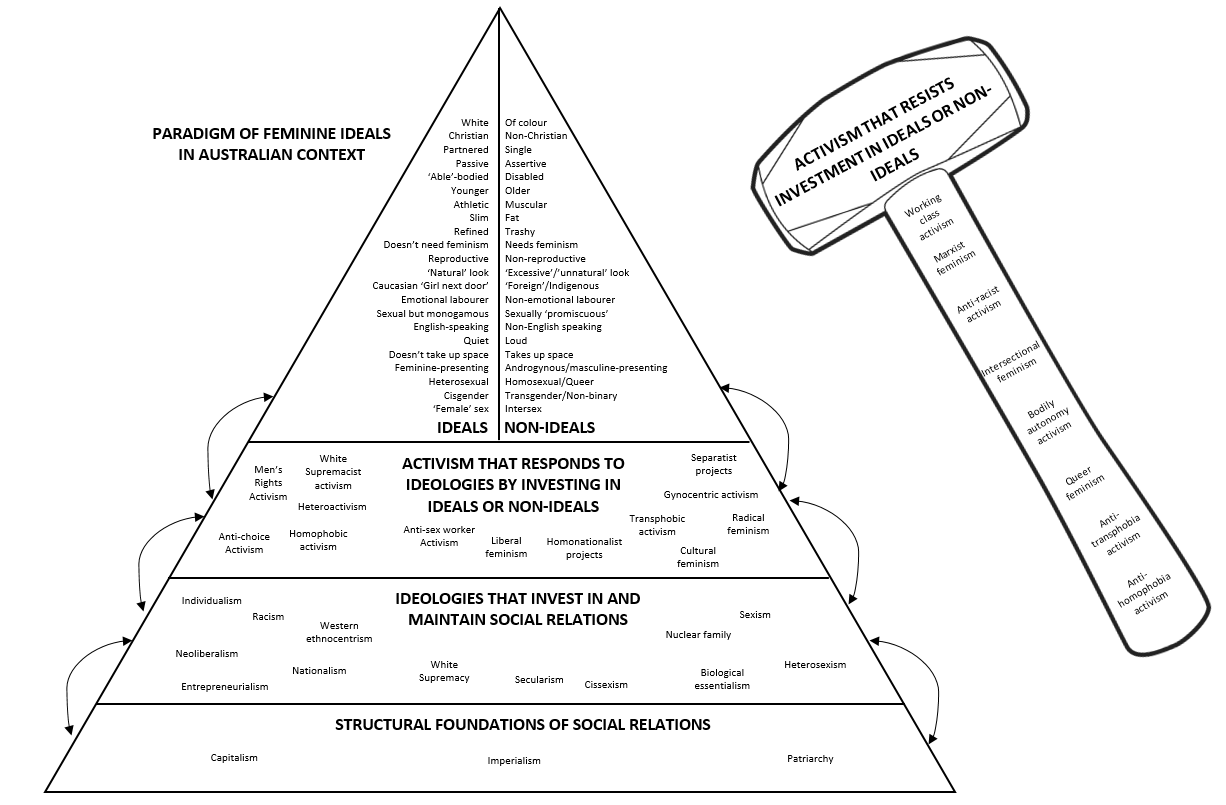

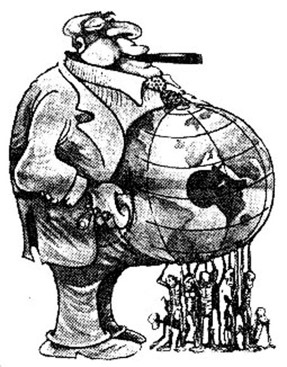

I like to think in visual terms, and the diagram above (click on it to enlarge) is an attempt to sum up how we might connect structure, activism, and norms in a useful way. I’ve included a hammer here as a kind of nuanced update to that “If I had a hammer” image.

I like to think in visual terms, and the diagram above (click on it to enlarge) is an attempt to sum up how we might connect structure, activism, and norms in a useful way. I’ve included a hammer here as a kind of nuanced update to that “If I had a hammer” image. At the very base are the “structural foundations”, which accounts for the economic, colonial, and gendered power structures that are the foundation of the dominant organisation of social relations in this context. Flowing from this foundation, but also feeding back into it, are the dominant ideologies that invest in and maintain these social relations. For example, neoliberalism is an ideology that supports capitalism. Similarly White supremacy is an ideology that supports imperialism. Flowing from this, there are various forms of activism that respond to these ideologies in ways that either bolster these ideologies or reject them. The activism that bolsters these ideologies also works toward cementing what is understood as the “ideals”.

At the very base are the “structural foundations”, which accounts for the economic, colonial, and gendered power structures that are the foundation of the dominant organisation of social relations in this context. Flowing from this foundation, but also feeding back into it, are the dominant ideologies that invest in and maintain these social relations. For example, neoliberalism is an ideology that supports capitalism. Similarly White supremacy is an ideology that supports imperialism. Flowing from this, there are various forms of activism that respond to these ideologies in ways that either bolster these ideologies or reject them. The activism that bolsters these ideologies also works toward cementing what is understood as the “ideals”. It is clear for example, that

It is clear for example, that  Perhaps this is what might mark out a new wave of (feminist and other) activism around femininity: challenging gender ideals without investing in non-ideals as the political response. From such a perspective, there is no femininity that is “empowered”. Power is exerted and ideals are enforced, but the reaction to this is to focus on the structural foundations and their ideological props rather than the individual effects alone (which might for some involve complicated attachments).

Perhaps this is what might mark out a new wave of (feminist and other) activism around femininity: challenging gender ideals without investing in non-ideals as the political response. From such a perspective, there is no femininity that is “empowered”. Power is exerted and ideals are enforced, but the reaction to this is to focus on the structural foundations and their ideological props rather than the individual effects alone (which might for some involve complicated attachments).

The first is from trans-exclusionary radical feminist types, who conflate gay male culture with drag queens with transgender identity. Such perspectives see gay men, drag queens, and trans women as responsible for propping up fantasies of femininity that only serve to oppress women. Germaine Greer famously stated in The Female Eunuch 1970: “I’m sick of being a transvestite. I refuse to be a female impersonator. I am a woman, not a castrate”. Greer’s suggestion here is that there is some form of “natural” womanhood that can be liberated from the dictates of culture. Similarly, and more recently, Sheila Jeffreys has even argued that drag kings distort lesbian culture and the celebration of “natural” womanhood. She writes: “If the suffering and destruction of lesbians is to be halted then we must challenge the cult of masculinity that is evident in such activities as drag king shows”. These views are rife with homophobia and transphobia, as well as massive conflations and wild leaps that see men, masculinity, and femininity, as the true oppressors of women.

The first is from trans-exclusionary radical feminist types, who conflate gay male culture with drag queens with transgender identity. Such perspectives see gay men, drag queens, and trans women as responsible for propping up fantasies of femininity that only serve to oppress women. Germaine Greer famously stated in The Female Eunuch 1970: “I’m sick of being a transvestite. I refuse to be a female impersonator. I am a woman, not a castrate”. Greer’s suggestion here is that there is some form of “natural” womanhood that can be liberated from the dictates of culture. Similarly, and more recently, Sheila Jeffreys has even argued that drag kings distort lesbian culture and the celebration of “natural” womanhood. She writes: “If the suffering and destruction of lesbians is to be halted then we must challenge the cult of masculinity that is evident in such activities as drag king shows”. These views are rife with homophobia and transphobia, as well as massive conflations and wild leaps that see men, masculinity, and femininity, as the true oppressors of women. I don’t have much time for these views, which encourage us to believe that the biggest threats to women are trans women, drag queens, and gay men. This view distorts Marxist theory to argues that men in particular are *the* class that oppresses women, and sees the liberation that is to be won as a liberation from “gender”. Luckily the currency of radical feminism in academic spaces seems to be waning. But when overall activist struggle in society is low, it is easy for people to slip into arguing that we are each other’s problem, that if only we could free ourselves from gender we’d be truly liberated. It’s a much easier argument to make than organising to transform the fundamental economic arrangement of society, and it makes space for all kinds of class collaboration between powerful women and poor women alike (even if it means at the end of the day that power doesn’t actually shift).

I don’t have much time for these views, which encourage us to believe that the biggest threats to women are trans women, drag queens, and gay men. This view distorts Marxist theory to argues that men in particular are *the* class that oppresses women, and sees the liberation that is to be won as a liberation from “gender”. Luckily the currency of radical feminism in academic spaces seems to be waning. But when overall activist struggle in society is low, it is easy for people to slip into arguing that we are each other’s problem, that if only we could free ourselves from gender we’d be truly liberated. It’s a much easier argument to make than organising to transform the fundamental economic arrangement of society, and it makes space for all kinds of class collaboration between powerful women and poor women alike (even if it means at the end of the day that power doesn’t actually shift).

So that’s why it’s kind of surprising to hear people within queer communities suggesting now that drag, in its mainstream formations, is a problem. From this perspective drag, if performed by ostensibly

So that’s why it’s kind of surprising to hear people within queer communities suggesting now that drag, in its mainstream formations, is a problem. From this perspective drag, if performed by ostensibly