Move over bury your gays, there’s a new trope in town and it’s about murderous bisexual chaos. (Note: some spoilers below for Passages, Poor Things, Saltburn and Love Lies Bleeding – I’ve tried to make it obvious where I discuss each so you can skip specific films you haven’t seen).

Not long ago I was reading through my high school diaries and found an entry musing on whether I was bisexual. I was sixteen. I did not use the word of course, I simply – coded and cautiously – mentioned that I had read an article in Cosmopolitan magazine about women who also like men and women both, and “y’know, maybe that’s me”. Skip forward several decades of grappling with my sexual identity, literally writing a PhD about being queer femme, and becoming a scholar who works on queer theory and sexuality… I am (fingers crossed) finally feeling pretty at ease with calling myself bisexual.

Sure we have the least exciting flag, but a few key insights for me have been: my affinity with other bisexuals (we just get each other, we see each other); the recognition that my desire does not transcend gender, but rather, is for all the genders (so many! I love them all! So hot!); that bisexual experience is about recognising shame that goes in multiple and maybe unexpected directions (e.g. feeling bad about having heterosexual desires); that the reality of homophobia deepens biphobia as we split into camps to save ourselves, but the need to have the grace to understand these structuring forces. Of course all of the angst I have grappled with over the years is probably just because I am a millennial – it seems that Gen Z are much more comfortable with their gender and sexual fluidity.

But what of bisexual representation in these shifting times? I last reflected on this question in 2019 (“Twenty BiTeen”). Back then I concluded that negative tropes about bisexuality (of greediness, just a phase, and straight privilege) were, in a very small strand of emerging bisexual representation, starting to be reworked and resisted. In 2022 I also wrote a paper about bisexuality as “the refusal to refuse”, aka the refusal of choosing a single monosexual line of desire. In part this paper looked at the distinction between the “bury your gays” trope where homosexuality is represented as a tragedy (the gay character dies), versus straight rom coms where heterosexuality is represented as an inevitable comedy (replete with failure). I argued that in contrast bisexuality was rarely intelligible at all – neither tragedy or comedy, simply an impossibility.

But since writing these pieces, something new has emerged. Enter: the disaster bisexual.

A disaster bisexual is, just as it suggests on the can, loosely defined as a bisexual character or person who has chaotic energy or causes chaos. It seems to be a term used with some affection (“oh what a disaster bisexual!”) and often personal identification (“I’m such a disaster bisexual!” – to which everyone replies “yes”). The disaster bisexual is not your typical queer-coded villain, but rather, an anti-hero. The term seems to pleasurably press the bruise of internalised biphobia. When you cannot corral your desires into a neat monosexual storyline, this can feel chaotic.

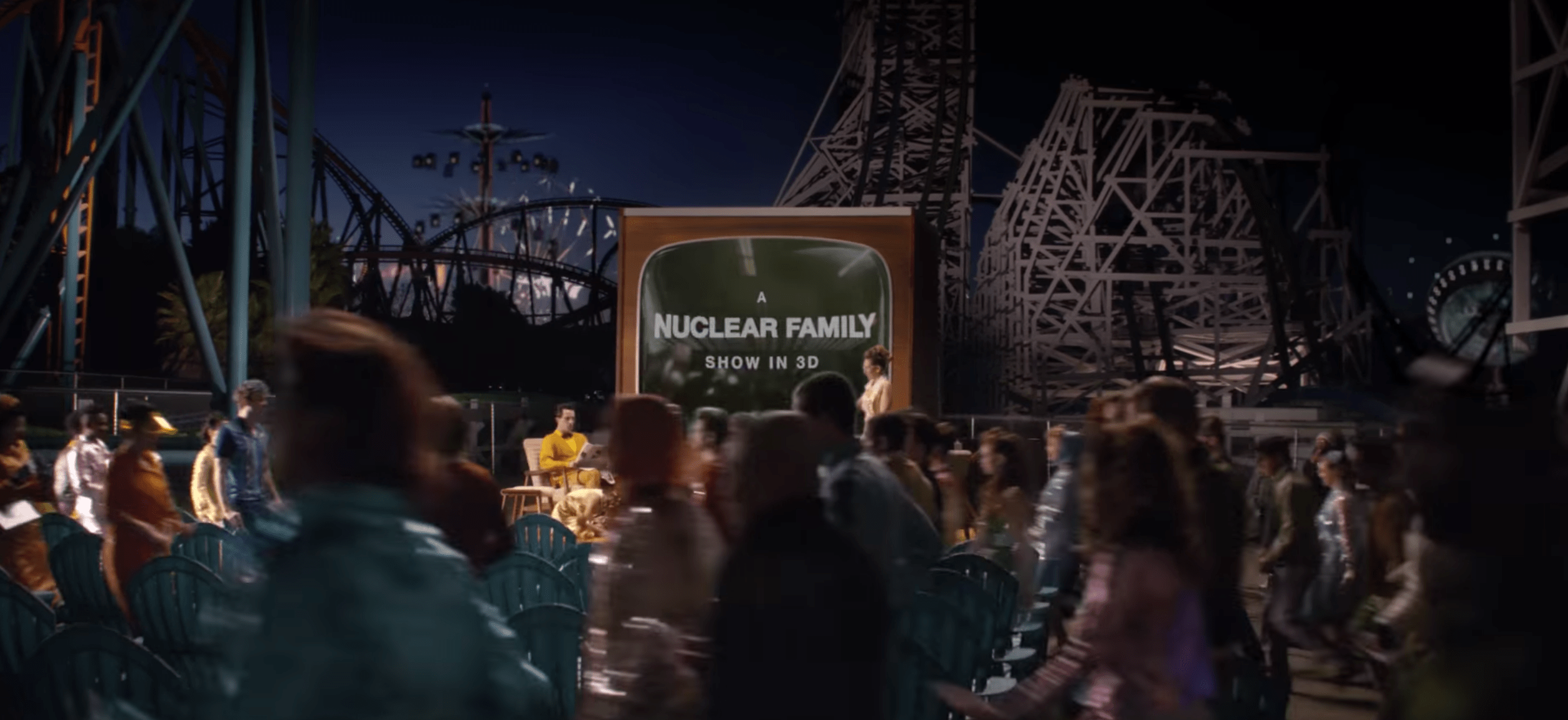

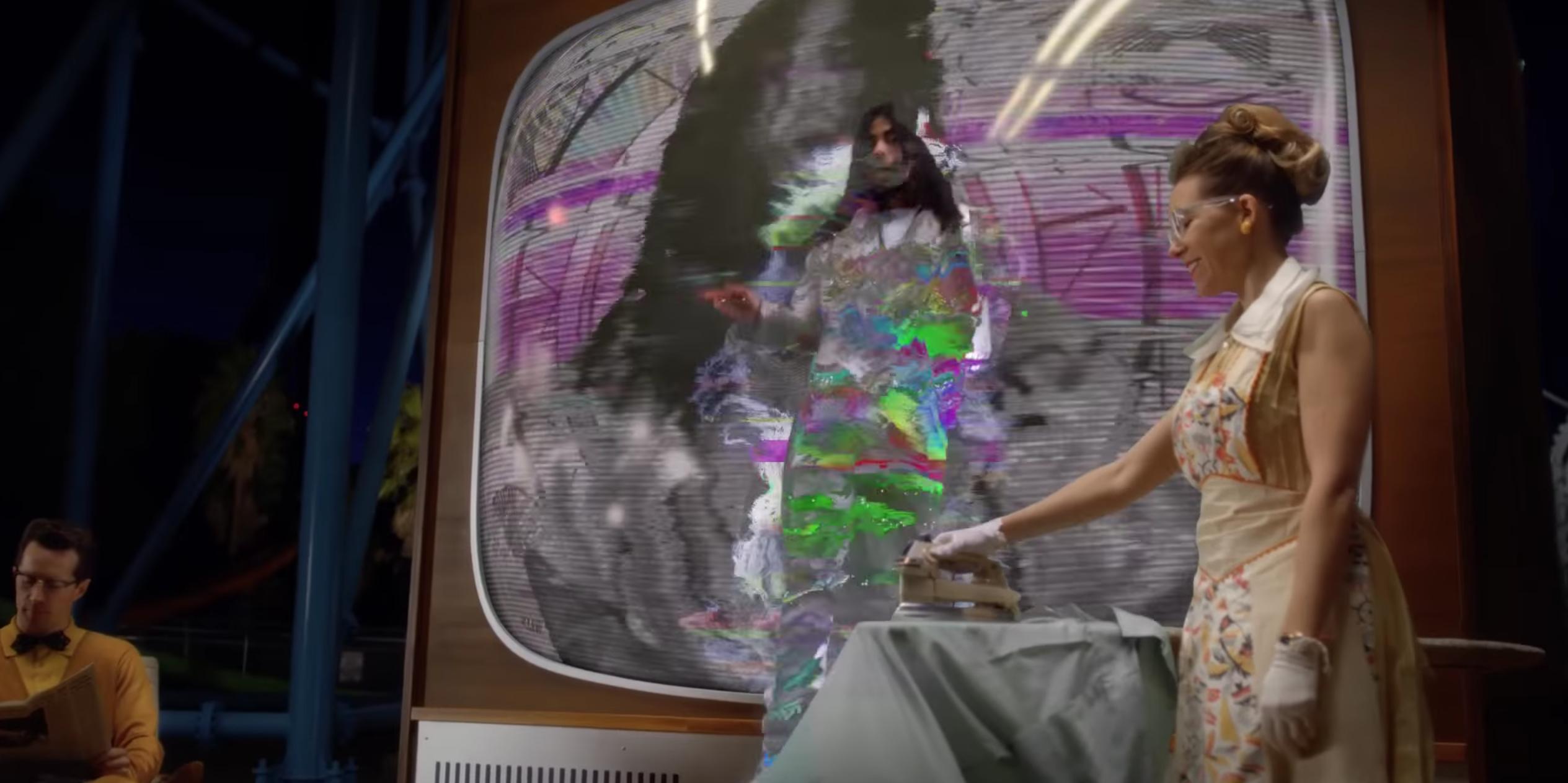

According to the internet, the term originated from a D&D meme about sexuality in 2017, but it really took off as a concept in wider circulation in 2022/2023. I would argue that we are now seeing echoes of this discourse in representation on screen, in films like Passages, Poor Things, Saltburn and Love Lies Bleeding (and so many more I have not had the chance to see yet!). Notably in none of these representations is the word “bisexual” used, the characters are simply depicted as having sex with people of multiple genders. This continues a long trend in representation where bisexual desire is represented but not named.

However, importantly, these representations take the disaster bisexual into sinister territory. While queer publications like Them last year lauded the rise of “the nuanced bi characters we’ve been waiting for” I was somewhat perplexed by this celebratory tone. Journalist Billie Walker suggested that “It’s not that we don’t want bisexuals to do bad things on screen. We just want them to do more interesting bad things, and for more interesting reasons”. Hmmm. Let’s take a look at some examples…

I saw the French romance/drama film Passages at the Melbourne Queer Film festival in 2023. On the night it was introduced by festival curator Cerise Howard as addressing the historical gap in programming bisexual representation, to which (me included) the audience whooped and cheered. At the end of the film I turned to the person I was with and laughed “well…we wouldn’t call it positive bisexual representation would we!” In the film the main character Tomas takes a bisexual wrecking ball to his life and loves with such chaos that by the end of the film you are cheering his downfall. Walker suggests that it would be a “lazy” reading of the film to see Tomas’ bisexuality as the cause of crisis in the film, rather than look to his egotism. But sometimes surface readings are the most important to understanding how tropes congeal. The most obvious interpretation is that Tomas is a disaster bisexual, leaving a trail of emotional carnage in the lives of the monosexual characters who foolishly love him.

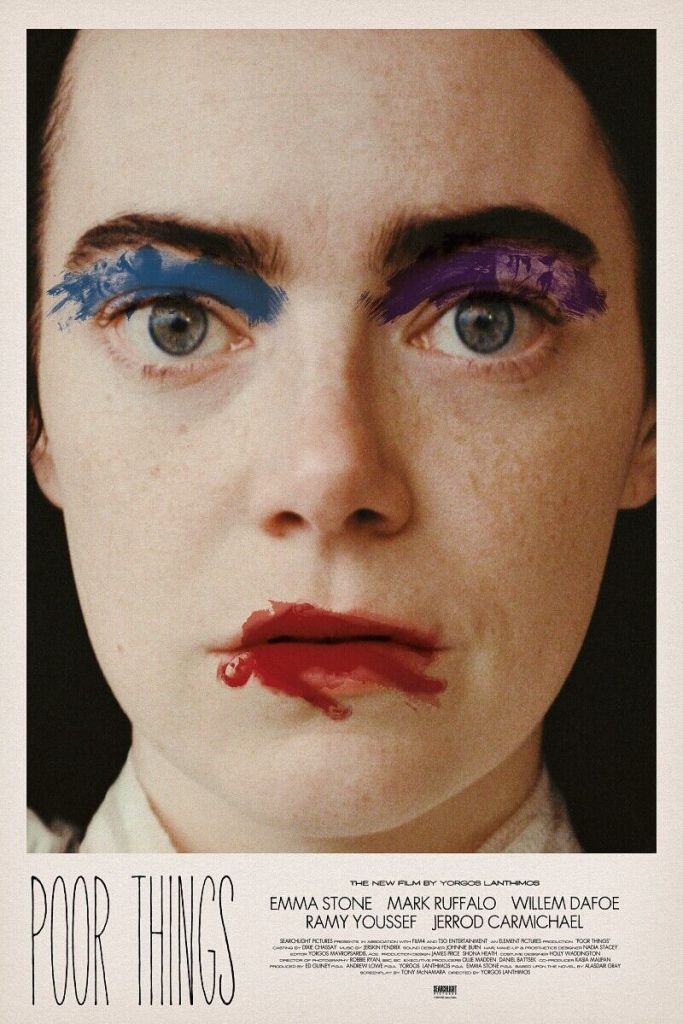

Similarly in science-fiction comedy/drama Poor Things, the sexual exploits of main character Bella are depicted as leaving destruction in her wake. Much of the film focuses on Bella developing a sense of self through her sexual adventures. She is a kind of Frankenstein’s monster, a gothic vehicle for representing society’s repressed desires. While she is the centre of the film, and we are essentially on Bella’s side (especially as she escapes the clutches of both wimpish and controlling men), she is also violently dangerous: unpredictably squashing, stabbing, or surgically destroying those in her path. Notably at the end we see Bella living in some kind of polyamorous bisexual utopia (albeit one with a slightly disturbing goat).

On violence, we can turn here to black comedy thriller Saltburn where our central disaster bisexual is perhaps the most ominous of all. Oliver is not simply violent, but a pathological liar and epitome of destructive Dionysian desire. Oliver lusts over the bodily and earthly – cum, blood and literal dirt – and it is at once disturbing and entertaining. Oliver is both compelling and scary. He is close to the material and earthly, and just as uncontrollable. At the end he is alone and happy, and everyone else is dead.

Finally, in romance thriller Love Lies Bleeding, our central protagonists are Lou and Jackie/Jack. While Lou is assuredly gay, and wary of sleeping with Jack in case she is just a “curious” straight, Jack notes that she likes “both” men and women. Arguably the central drama of the film is caused by a combination of Lou’s brother in law’s domestic violence, and the fact that Jack has slept with the brother in law. When Jack gets vengeance it is ambiguous as to whether she is trying to right the wrong of the brother in law’s violence, or, atone for the hurt caused by her bisexual exploits. While Jack is depicted throughout as uncontrollable, unpredictable, and totally chaotic, Lou is remarkably together and always cleaning up after her.

Of course there are many other things to say about these films that are not purely about the disaster bisexuality of it all – about rage and families and vengeance and kinks – but it is telling that all of these disaster bisexual films rather unusually mix up genres of comedy/romance with drama/thriller. This speaks to bisexuality sitting at the intersection of heterosexual (comedy) and homosexual (tragedy) tropes: an uncomfortable mash. As such these films do not end in classic “tragedy”, rather, we see the bisexual emerging intact despite the rubble from which they emerge.

Yes, these films are not all “about” bisexuality but in all of these films bisexual desires are at the heart of the drama and often the cause of crisis. Many of the scenes in these films are also highly visceral, focusing on blood, sweat, vomit, cum, and the bodily, with varying levels of gore (with the exception of Passages which is simply sexy and sweaty, with great crop tops). The disaster bisexuals are the spark and conduits of this viscerality. Notably, all the disaster bisexuals are hot, really hot – and I am not just saying that because I am a bisexual attracted to everyone – I mean, alluring. We are meant to understand the appeal of the disaster bisexual, even as we are warned to be wary, if not afraid, of this seductive power.

On this note, it would be wrong, I think, to say that these representations of bisexuality are “bad”. This is probably my disaster bisexuality speaking, but it is way more fun to identify with the villain than have really happy unproblematic bisexual representation. And of course in selecting these films I have left out other key bisexual representations we have seen recently – such as in Heartstopper and Red, White and Royal Blue – where the bisexuals are not really chaotic at all, just attractive and nice.

My point is to question: should we “celebrate” representations of disaster bisexuals? I am not convinced. Rather, I think we should keep tabs on the disaster bisexual trope and how it is playing out, what this trope has to say about sexuality and desire, how these representations connect with broader sentiments and politics around sexuality, and perhaps most importantly, how these depictions make us bisexuals feel. As we watch, we should attend to whether it pleasurably presses the bruise, or, sometimes, digs a bit too far into the wound.

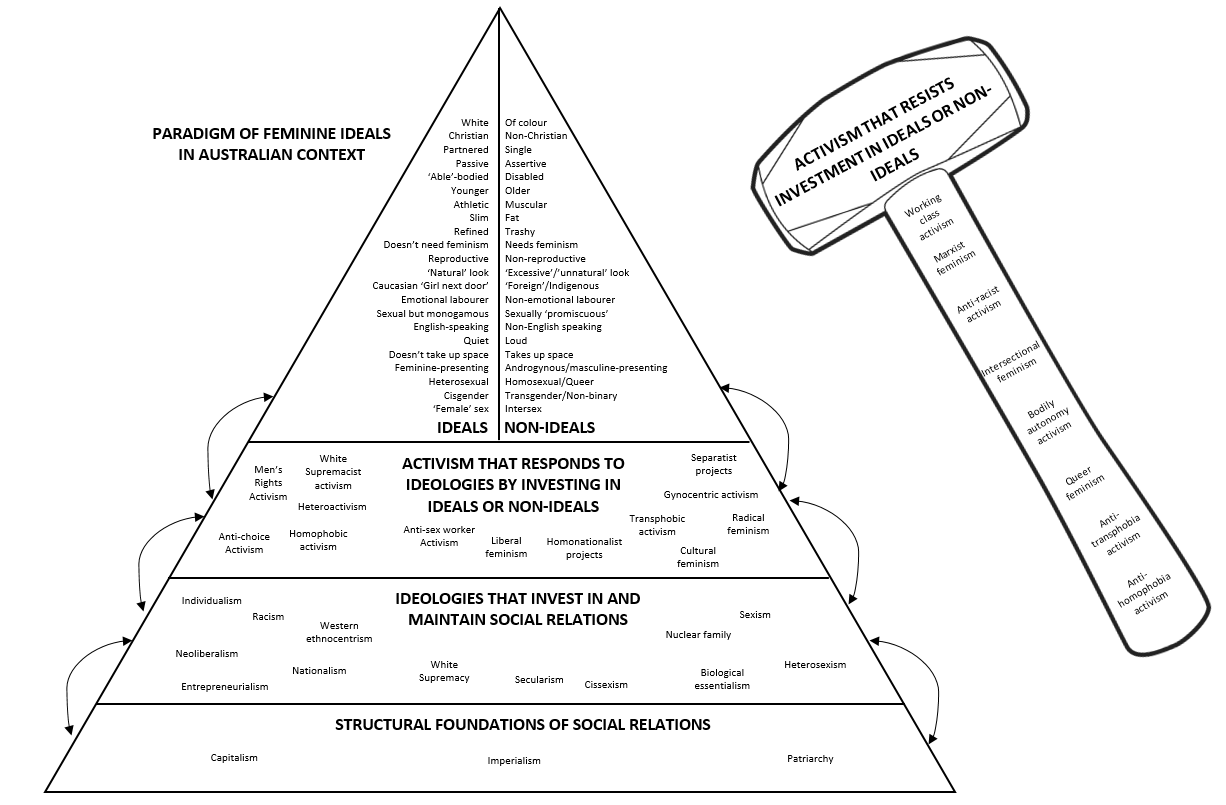

I like to think in visual terms, and the diagram above (click on it to enlarge) is an attempt to sum up how we might connect structure, activism, and norms in a useful way. I’ve included a hammer here as a kind of nuanced update to that “If I had a hammer” image.

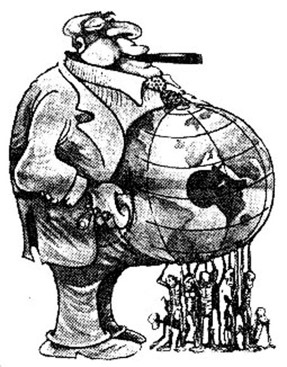

I like to think in visual terms, and the diagram above (click on it to enlarge) is an attempt to sum up how we might connect structure, activism, and norms in a useful way. I’ve included a hammer here as a kind of nuanced update to that “If I had a hammer” image. At the very base are the “structural foundations”, which accounts for the economic, colonial, and gendered power structures that are the foundation of the dominant organisation of social relations in this context. Flowing from this foundation, but also feeding back into it, are the dominant ideologies that invest in and maintain these social relations. For example, neoliberalism is an ideology that supports capitalism. Similarly White supremacy is an ideology that supports imperialism. Flowing from this, there are various forms of activism that respond to these ideologies in ways that either bolster these ideologies or reject them. The activism that bolsters these ideologies also works toward cementing what is understood as the “ideals”.

At the very base are the “structural foundations”, which accounts for the economic, colonial, and gendered power structures that are the foundation of the dominant organisation of social relations in this context. Flowing from this foundation, but also feeding back into it, are the dominant ideologies that invest in and maintain these social relations. For example, neoliberalism is an ideology that supports capitalism. Similarly White supremacy is an ideology that supports imperialism. Flowing from this, there are various forms of activism that respond to these ideologies in ways that either bolster these ideologies or reject them. The activism that bolsters these ideologies also works toward cementing what is understood as the “ideals”. It is clear for example, that

It is clear for example, that  Perhaps this is what might mark out a new wave of (feminist and other) activism around femininity: challenging gender ideals without investing in non-ideals as the political response. From such a perspective, there is no femininity that is “empowered”. Power is exerted and ideals are enforced, but the reaction to this is to focus on the structural foundations and their ideological props rather than the individual effects alone (which might for some involve complicated attachments).

Perhaps this is what might mark out a new wave of (feminist and other) activism around femininity: challenging gender ideals without investing in non-ideals as the political response. From such a perspective, there is no femininity that is “empowered”. Power is exerted and ideals are enforced, but the reaction to this is to focus on the structural foundations and their ideological props rather than the individual effects alone (which might for some involve complicated attachments). As

As  So the story goes: “it gets better”. This is a common refrain of LGBTIQ youth services in Australia. “It gets better” refers to the promise that when you leave school, you won’t have to deal with bullies any longer – you’ll be free to live your life as a happy LGBTIQ person. Now, for many of us, this isn’t totally wrong. Leaving the social intensity of the schoolyard and becoming independent from family units, can mean that we are able to find new communities of acceptance.

So the story goes: “it gets better”. This is a common refrain of LGBTIQ youth services in Australia. “It gets better” refers to the promise that when you leave school, you won’t have to deal with bullies any longer – you’ll be free to live your life as a happy LGBTIQ person. Now, for many of us, this isn’t totally wrong. Leaving the social intensity of the schoolyard and becoming independent from family units, can mean that we are able to find new communities of acceptance. But how cruel might this hopeful promise be, when bigotry can be canvassed as state-sanctioned “legitimate debate”, as we are seeing now? When homophobic and transphobic ideas are not originating from the schoolyard itself – as we know,

But how cruel might this hopeful promise be, when bigotry can be canvassed as state-sanctioned “legitimate debate”, as we are seeing now? When homophobic and transphobic ideas are not originating from the schoolyard itself – as we know,  As

As  But cruel is the optimism of the segments of the “yes” campaign that refuse to confront the homophobia and transphobia emerging in the debate, and instead seek to win hearts and minds on the basis of respectability, normality, and the idea that “love” is indeed “love”. As Berlant argues, it is a cruel optimism that operates where we live with the toxic conditions of the present labouring under the view that the future will “somehow” deliver something better.

But cruel is the optimism of the segments of the “yes” campaign that refuse to confront the homophobia and transphobia emerging in the debate, and instead seek to win hearts and minds on the basis of respectability, normality, and the idea that “love” is indeed “love”. As Berlant argues, it is a cruel optimism that operates where we live with the toxic conditions of the present labouring under the view that the future will “somehow” deliver something better. And indeed it is cruelly optimistic to imagine what that future will entail if we do not question the social constitution of futurity in the first instance. As

And indeed it is cruelly optimistic to imagine what that future will entail if we do not question the social constitution of futurity in the first instance. As  This is precisely what we have seen playing out for over a decade, albeit more sharply in recent times, in the marriage equality debate. While the right have repeated the refrain, “think of the children”, the left too have taken up this mantle, constantly leaning on statistics about the welfare of queer youth or children from queer families in order to make a point of the utter sameness of the child under queer circumstances. In this envisioning, the queer child doesn’t queer the future, rather, the queerness of the child is contained in order to suggest that there is very little threat – only a slight extension – to the more conservative vision.

This is precisely what we have seen playing out for over a decade, albeit more sharply in recent times, in the marriage equality debate. While the right have repeated the refrain, “think of the children”, the left too have taken up this mantle, constantly leaning on statistics about the welfare of queer youth or children from queer families in order to make a point of the utter sameness of the child under queer circumstances. In this envisioning, the queer child doesn’t queer the future, rather, the queerness of the child is contained in order to suggest that there is very little threat – only a slight extension – to the more conservative vision. As the recent

As the recent  We might wonder about the astringency of Edelman’s anti-social thesis, in light of the fact that attachment to “same-sex marriage” is currently being enacted by many as a mode of survival. Many have thrown themselves into fighting for a yes campaign precisely in order to assist a striving toward a “getting better”. We might also question the limits of Edelman’s radical presentism and anti-futurity, and if a different kind of future envisioning might be possible without a cruel investment in inevitable progress.

We might wonder about the astringency of Edelman’s anti-social thesis, in light of the fact that attachment to “same-sex marriage” is currently being enacted by many as a mode of survival. Many have thrown themselves into fighting for a yes campaign precisely in order to assist a striving toward a “getting better”. We might also question the limits of Edelman’s radical presentism and anti-futurity, and if a different kind of future envisioning might be possible without a cruel investment in inevitable progress. As

As  Similarly

Similarly  But in making the negativity at the heart of things public rather than private, we can also become targeted as the problem rather than merely pointing out the problem. As

But in making the negativity at the heart of things public rather than private, we can also become targeted as the problem rather than merely pointing out the problem. As  While we focus solely on concepts like fairness and kindness, positivity, good stories, the “good homosexual”, or the “unqueer queer child”, the bad feelings at the heart of the marriage equality debate remain occluded and politically impotent. To fail to recognise and name the homophobia and transphobia that are proliferating under conservative discussions in the marriage equality debate is to inadvertently reiterate a narrative of a heteronormative future where “it gets better”. To engage in a queer hopefulness then, is not to shy away from negativity, but rather, to embrace the possible world that it reveals to us.

While we focus solely on concepts like fairness and kindness, positivity, good stories, the “good homosexual”, or the “unqueer queer child”, the bad feelings at the heart of the marriage equality debate remain occluded and politically impotent. To fail to recognise and name the homophobia and transphobia that are proliferating under conservative discussions in the marriage equality debate is to inadvertently reiterate a narrative of a heteronormative future where “it gets better”. To engage in a queer hopefulness then, is not to shy away from negativity, but rather, to embrace the possible world that it reveals to us. It is only in confronting those elements of the present that we would rather deny, from which a truly utopian vision might emerge. In this case, my educated hope is that we will have a marriage equality debate that confronts homophobia and transphobia, that embraces gender and sexual diversity, and that makes space for the LGBTIQ community well beyond the question of marriage.

It is only in confronting those elements of the present that we would rather deny, from which a truly utopian vision might emerge. In this case, my educated hope is that we will have a marriage equality debate that confronts homophobia and transphobia, that embraces gender and sexual diversity, and that makes space for the LGBTIQ community well beyond the question of marriage.

S is for

S is for